Home »

Bud Abbott Bombed The Tirpitz

By Elinor Florence

Based on a personal interview with Bud Abbott, plus a newspaper article written for The Cranbrook Townsman by freelance writer Ferdy Belland.

Bud Abbott of Cranbrook was just 23-years-old when he strapped himself into his cockpit, took off from the deck of an aircraft carrier in the North Sea, and set off into aerial combat for the very first time. His target: the deadliest German battleship ever built.

Philip “Bud” Abbott was born on January 26, 1921 in Southend-on-Sea, 40 miles east of London. His father was a policeman, and he had four siblings.

In the early days of the Second World War, Bud worked as an insurance clerk, commuting to London each day on the steam train. He joined the Royal Navy in 1941, at the age of 20.

“My first choice was the navy,” he said. “I thought if I wasn’t accepted into the navy that I would try the Royal Air Force. I managed to end up in the Royal Naval Air Force, also known as the Fleet Air Arm. I thought it was an ideal combination, to be in the navy and to be flying!”

Not only Bud but all four of his siblings served. Bill joined the British Army (and lost his leg at Caen), Margaret was in the Women’s Army Corps, Gwen in the Land Army, and Don also served in the navy. Here’s a photo of four of them, missing only Gwen.

Bud was stationed in northern Scotland, where the Home Fleet of the British Navy was based, flying anti-submarine patrols.

“I mostly flew the Swordfish, an old-school biplane, fixed undercart, no hood, no canopy, open air, no radio. Quite a neat, light little plane. We called them “Stringbags” since the critics said they were tied together with haywire.”

There were three men in a Swordfish – the pilot, the observer-navigator, and the radio operator-tail gunner.

The main British naval base in Scotland was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands. “The entire Home Fleet would gather in there in comparative safety,” he said. “I flew off several aircraft carriers: the Illustrious, the Indomitable, the Victorious, the Furious, and others.”

The tricky part was learning how to take off and land on the deck of an aircraft carrier. Both the speed of the carrier and the speed of the wind were crucial factors. Bud explained: “You need a certain speed to get airborne. With the ship steaming at 20 knots into a surface wind of 20 knots, providing 40 knots over the deck, in a Swordfish you only needed another 10 knots to get airborne.”

He went on to fly a Fairey Albacore, considered luxurious because it had a sliding canopy so the crew was inside out of the weather. Later he progressed to the Fairey Barracuda. “Our planes were called TBR: Torpedo-Bomber-Reconnaissance. But reconnaissance was our principal duty.”

This photo (right) shows a row of Seafires lined up on deck, ready for takeoff. (Photo courtesy Bud Abbott).

This photo (right) shows a row of Seafires lined up on deck, ready for takeoff. (Photo courtesy Bud Abbott).

Bud was assigned to convoy work in the North Sea and the Atlantic. These patrols kept watch for submarines that were lurking underwater, often inflicting fatal wounds on the merchant ships. These convoys came from North America over Iceland and into the Russian ports, mainly Murmansk and Archangel, where their supplies were desperately needed.

For weeks at a time, he lived aboard huge aircraft carriers each accommodating thousands of men. “We’d fly half-way across the Atlantic and back again.”

In spite of his constant patrols, Bud never dropped any depth charges on submarines. “The U-Boats were generally very wary and stayed down and deep, out of sight. They were wise enough not to show themselves.” As a consequence, the subs were unable to fire their torpedoes.

This photo (left), courtesy of Bud Abbott, shows an aircraft hovering over a carrier.

This photo (left), courtesy of Bud Abbott, shows an aircraft hovering over a carrier.

Bud did have his share of close calls. In 1944 he was stationed on the northern coast of Scotland, one of the few level patches in that mountainous terrain.

Ordered to practise target bombing at night, Bud flew his Barracuda ME 149 fifty miles up the coast where a floating target was anchored. After dropping his bombs, he headed for home, flying low over the water to test out the plane’s new radio altimeter.

“Obviously the altimeter wasn’t accurate – there was an ominous crunch as we hit the water and bounced back out again! The plane, hovering just above the water, enjoyed the experience and was determined to go back in again. I, of course, had other ideas!

“There were real problems: the plane had become nose-heavy, and the throttle friction nut so loose that the throttle snapped shut. Big panic! To keep the plane in the air, I had to hold the throttle wide open, tighten the friction nut, pull back hard on the control column and trim the elevators all at the same time. Fortunately the radio operator gathered that something was amiss and sent out a Mayday call.”

The plane was impossible to control and drifting dangerously close to the rocky shore. “I very gingerly steered back over the water and headed down the coast toward the airfield, keeping close to the shore in case we had to swim. It was very dark and the sea looked ominously black and cold. Over those 50 anxious miles back to base, the plane climbed bravely to 400 feet, vibrating violently, protesting all the way.

“Finally we drew level with the airfield and turned inland. They had received our Mayday call and were ready – the runway was lighted and the crash wagon standing by. Tottering barely above the stall, I made a slow half-circuit and dropped onto the runway with a huge sigh of relief. The engine did the same and promptly died. A tractor towed us into the hangar where we climbed out, patted the aircraft and headed to the bar for a quick one. We needed it!”

The following morning, Bud learned that the aircraft was a total loss. “Its belly was severely crumpled, the plastic radar bubble obliterated, the six blades of its wooden propeller were broken off and the air intakes plugged with wood chips. Of the heavy bolts holding the engine to the frame, three had sheered off and only one was intact. No wonder the aircraft vibrated so wildly all the way home!”

Accidents were not uncommon, although Bud said nobody from his squadron was lost taking off or landing. If the aircraft did not get airborne on takeoff, the crew would have to ditch it in the drink and be picked up by an escorting destroyer. Here’s a photo of a Seafire landing badly, and just slipping overboard off the deck. (Photo courtesy of Bud Abbott).

Accidents were not uncommon, although Bud said nobody from his squadron was lost taking off or landing. If the aircraft did not get airborne on takeoff, the crew would have to ditch it in the drink and be picked up by an escorting destroyer. Here’s a photo of a Seafire landing badly, and just slipping overboard off the deck. (Photo courtesy of Bud Abbott).

But the most famous, and the most frightening, incident in Bud’s flying career took place on April 3, 1944 when he was ordered to bomb the Tirpitz.

The target of the attack by four Royal Navy squadrons, including Bud’s squadron RN 827, was what British officers bitterly referred to as “the Iron Whore.”

The Tirpitz was the largest battleship ever built by a European navy, the sister ship of the dreaded Bismarck. Since the destruction of the Bismarck in 1941, the Tirpitz had been holed up in a Norwegian fjord, seldom venturing forth to attack Allied ships, but still a great menace.

“The whole time it was anchored in Norway, it presented an enormous threat, to the point where it basically tied up the Home Fleet in Scapa Flow, watching for this damned thing to come out. And if it did come out and got into the shipping lanes, it would create enormous havoc.”

The Tirpitz had been launched in 1939. The statistics are still impressive: 823 feet long and 118 feet wide, the ship displaced 53,000 tons fully loaded. The 163,000-horsepower engine made her the fastest battleship afloat. Her crew complement was more than 2,000 officers and men.

Said Bud: “I understand that the officers and crew of the Tirpitz were all just moping around there in this idiot fjord, doing nothing, and thoroughly bored. They would be anxious to get some action.”

And action they got, although the attack came as a total surprise.

The British Admiralty had initiated a secret plan called Operation Tungsten. Four squadrons were to take off from two separate aircraft carriers and launch a surprise attack.

“I’d been stationed on the Victorious at that time, but we were temporarily switched over to the Furious. The squadrons were split between the two ships so we could all take off simultaneously. I went over with the rest of my squadron to the Furious.

“The Furious was a weird ship, the oldest aircraft carrier afloat at that time. She was laid out in 1915, but she wasn’t originally designed as an aircraft carrier – she was refit in the 1920s. And her deck was very uneven, like a logging track!”

For this mission, Bud wasn’t flying his Stringbag, but a Fairey Barracuda. The attack took place in two separate waves. Twenty-one Barracudas flew in each wave, along with 40 escort fighters – Hellcats, Wildcats, Corsairs, and Seafires.

“I was in the second wave. The first wave flew off at the break of dawn and got through to the target without any problems. They weren’t expected. They dropped their bombs and flew back to the carriers. Got through unscathed, with no casualties.”

But there was an hour’s lapse between waves. It took time to raise the next round of Barracudas to the deck, fuelled and armed. And the bombers were slow and heavy compared to the fighters.

“Some of those fighters, especially those beautiful gull-winged Corsairs, flew off the carriers like a damned rocket. Quite impressive. While us, the underpowered heavily-laden bombers, were crowded far aft on the flight deck. We had to gun the engine fully to get airborne before reaching the ship’s bow.”

Once his aircraft laboured into the sky, Bud and his squadron flew low over the water to avoid detection. “So there we were, my rear gunner Petty Officer Gallimore and my navigator Sub-Lieutenant Bill Peck and myself, crammed into this Barracuda. We flew in for the coast barely 50 feet above the waters to avoid German radar.

“The Tirpitz was 120 miles from our fleet and when we reached the Norwegian coastline, we all climbed steeply to about 9,000 feet altitude and flew inland between the mountains. It was a bright, clear day at the end of winter. The mountains were gleaming white with snow, and the delightful scenery was very impressive.”

The scenery was forgotten as Bud neared his target. “We finally rounded the last turn at the far end of Kaafjord and actually saw the Tirpitz anchored in harbour,” Bud said. “There she was!”

The first wave had inflicted significant damage on the Tirpitz. Several bombs had landed on the ship’s main deck, but none of the big 1,600-pound armour-piercing bombs managed to breach the lower armour in the hull.

“The Germans were spitting mad, and had a good hour to prepare themselves for any follow-up attacks. We were immediately met with a heavy barrage of anti-aircraft fire, and dozens of Luftwaffe intercepts raced at us out of the sun!

“Our particular squadron, I think there were nine of us, peeled off from the main flight and began our attack run. We could see the ship, but much of it was clouded in by an artificial fog, created by the shore-mounted German smokescreen generators. Down in this fjord, this deep hole if you will, it was difficult to see!

“But each Barracuda had three 500-pound bombs and we had to deliver them. So down we dove, our Barracuda shuddering through the explosions of the incoming anti-aircraft shells. It was difficult to keep aiming straight.

“Our escort fighters were dogfighting like mad with the Messerschmitts in the skies above us, and other fighters were below us, strafing the Tirpitz’s deck and attacking the anti-aircraft batteries on shore.

“We dropped our bombs, made our strike, and then banked off hard. We flew away as fast and low as we could get, racing back to the carriers. It all happened so fast.

“Our squadrons got out of the skirmish quite lucky, actually. We only lost nine airmen and four aircraft, all told. It could have been a heck of a lot worse, but the Tirpitz’s smokescreen actually worked double-duty in our favour. The German anti-aircraft gunners couldn’t see us and were all firing blind into the sky.”

The lead image above, taken from one of the other aircraft, shows the Tirpitz on fire. (Photo courtesy of Bud Abbott).

But the operation was far from over.

“The weather suddenly became quite cloudy. It was now difficult to find our ship, and we were still over enemy territory. No one knew if the Luftwaffe would chase us down. And we were flying under complete radio silence. Radio communication was absolutely forbidden.

“We’re up there in the clouds, and the carrier was somewhere down underneath the clouds. Some of the pilots couldn’t find the ships, and had to ditch in the North Sea and make their way back to Norwegian shore, where they had to surrender to the rather unsympathetic German troops!”

To his great relief, Bud spotted the Furious through the clouds. But he still had to land his aircraft.

“Our approach to landing back on the carrier decks was to come in high, just above the stall, as opposed to the American method where they bore in just above the waves. The stern of the carrier would be heaving up and down in the choppy seas, as much as 30 feet of movement high and low. You ran the risk of simply crashing hard and flat into the ass end of the carrier if you didn’t have your wits about you. We came in at half-throttle, just above the stall, and came down almost in the centre of the deck, where there was a minimum of movement, and you hoped to hell your braking hooks would catch the deck cables!”

Happily, Bud landed the aircraft in one piece. Operation Tungsten was deemed a success. Although the Tirpitz hadn’t been destroyed, she had been severely crippled and would be out of service for a long time. Hundreds of men on board the Tirpitz had been killed or wounded including the commander Hans Meyer.

The Tirpitz never took to open seas again, and was ultimately destroyed a few months later, on November 17, 1944, by Royal Air Force bombers.

“It was a shame, really to have such a magnificent ship destroyed. It was a shame to have this sort of idiocy prevailing. The idiocy of war. It would be wonderful to see such a fine piece of naval history sitting pretty in some maritime museum.”

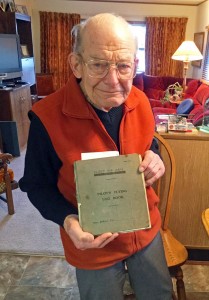

Like all good pilots, Bud has kept his logbook. Inside, there is a record of his attack on the Tirpitz on April 3, 1944 titled Operation Tungsten in Bud’s handwriting.

After that attack, Bud’s squadron returned to less dangerous duties. A year later, in April 1945, he was sent out to Ceylon. “Our mission was to tackle the Kamikaze pilots,” he said. “But their planes left us way behind. Our carrier Smiter was small and slow and most of the time there was no wind. That was the real hazard.” Fortunately the war in Asia ended a few months later.

“It was a good, clean life,” he says of his time in the Navy. “Much better than standing in mud up to your knees in the trenches.”

Bud stayed in the navy and spent a year in Northern Ireland, where he met his red-headed English wife Joan Goddard, who was serving in the Wrens. After his marriage he returned to the insurance business in London.

In 1957 the couple had two children when they decided to emigrate to Canada. Bud worked as an insurance agent in Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver before moving to Cranbrook, British Columbia, in 1960. The couple had two more children before divorcing in 1965.

His daughter Louise teaches social work at College of the Rockies in Cranbrook; son Christopher is a carpenter in Boulder, Colorado; daughter Rebecca is a retired realtor in Comox; and son Gregory teaches hairdressing in Victoria.

Bud remarried in 1967 but is now a widower who still drives his own car and lives alone in his own home. He’s a well-known figure in the community, as a former insurance agent, an amateur actor and a respected World War Two veteran.

“I’ve been here 55 years and I like it so much that I’m thinking of staying!” he said.

Bud came to Lotus Books in downtown Cranbrook on December 5, 2015 to visit me at a signing of my wartime novel, Bird’s Eye View.

On January 26 Bud Abbott will celebrate his 95th birthday. Have a very happy birthday, Bud, and thank you for your courageous contribution to the Allied victory!

Editor’s note: Happy birthday from Carrie and I, too, Bud! Thank you for your service and contribution to our world, big and small.

– Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

Elinor’s first historical novel was recently published by Dundurn Press in Toronto. Bird’s Eye View is the only novel ever written in which the protagonist is a Canadian woman in uniform during World War Two. The heroine Rose Jolliffe is an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. She spies on the enemy from the sky and makes several crucial discoveries. Lonely and homesick, she maintains contact with Canada through letters from the home front. The book is available through any bookstore including Lotus Books in Cranbrook, and also as an ebook from any digital book provider including Amazon, Kindle and Kobo. You can read more about the book by visiting Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com/birdseyeview

Elinor’s first historical novel was recently published by Dundurn Press in Toronto. Bird’s Eye View is the only novel ever written in which the protagonist is a Canadian woman in uniform during World War Two. The heroine Rose Jolliffe is an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. She spies on the enemy from the sky and makes several crucial discoveries. Lonely and homesick, she maintains contact with Canada through letters from the home front. The book is available through any bookstore including Lotus Books in Cranbrook, and also as an ebook from any digital book provider including Amazon, Kindle and Kobo. You can read more about the book by visiting Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com/birdseyeview