Home »

D-Day: The unhappiest man on the beach

By Elinor Florence

Seventy-one years ago today, Arthur Bradford’s Spitfire was shot down over Normandy, and he parachuted into the sea where he was promptly “rescued” by a landing craft, steaming towards the beach. He was unarmed, untrained, and very unhappy.

I interviewed Arthur Bradford at his comfortable home in Invermere, before he passed away in 1999. He was short in stature, with twinkling eyes, dry wit and the typical British habit of understatement. His experience on D-Day must have been horrendous, but he made it sound like a vaudeville comedy routine.

In my eyes, Arthur Bradford was a true British hero.

Arthur Thomas Bradford was born in Wales. In his usual self-deprecating style, he told me he didn’t want to go down the mines, so he attended university in Cardiff and became a teacher instead.

He moved to London and got a teaching job and, like all Welshmen, joined a rugby club.

In 1938, he said some fellows came along and offered members of the club “Learn to Fly for Half A Crown.”

“This seemed like a good deal, so not suspecting what we were being trained for, we learned to fly,” he said.

A year later, Arthur married an English girl and purchased a house outside Southampton.

A year later, Arthur married an English girl and purchased a house outside Southampton.

When war broke out he was called up and sent to Canada to train as a fighter pilot, under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, at Penhold, Alberta. (He told me this was what led him to emigrate to Canada after the war.) On his return to England he was stationed at RAF Biggin Hill, a fighter command air base.

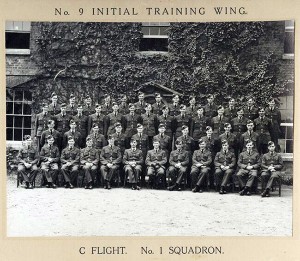

Arthur’s service record says that he was a Flight Sergeant Pilot in the Royal Air Force, seconded to the Royal Canadian Air Force where he served with Squadrons 401 (originally called No. 1 Squadron) and 410. In this group photograph, Arthur is standing behind the row of seated men, second from the left.

Arthur was one of “the few” who flew a Spitfire during the Battle of Britain, intercepting the Luftwaffe bombers as they came down the Thames River. The Royal Air Force successfully defended their country, often running to the aircraft still wearing their pyjamas, and drove back the German air force.

The expression is taken from Churchill’s famous speech about the Royal Air Force: “Never was so much owed by so many to so few.”

The expression is taken from Churchill’s famous speech about the Royal Air Force: “Never was so much owed by so many to so few.”

Arthur typically made light of his achievements. “I wasn’t a very good pilot – that’s why I’m here today. It was the good pilots who got killed.”

Nevertheless he shot down three Stukas, which were two-man German dive bombers.

“We were too busy trying to stay alive to be frightened.”

For the next couple of years, he was stationed at different air bases all over England. He and his wife had a baby son named Michael, and they decided

Southampton wasn’t safe.

“It got a terrible pounding. They were after the docks. Whenever the bombers went over to Manchester or another English city, they’d drop a few bombs on their way over and if they had any left on the way back, they’d drop them on Southampton.”

So Trudy took the baby boy and went to Wales, to live with the elder Bradfords, while Arthur continued to fly Spits. “They weren’t long range, but fortunately neither were the Messerschmitts.”

Finally, the Allies felt ready to wrest control of the European continent back from the Nazis, and it had been months in the making.

As dawn broke on June 6, 1944

Arthur was flying a last-minute reconnaissance mission over LeHavre, France.

His aircraft was painted with black and white “invasion stripes,” so the good guys could tell them from the bad guys.

He flew over the English Channel, past masses of troop-carrying gliders being towed by Halifax bombers. From his cockpit window, he could see an armada of around 7,000 ships approaching the French coast for the largest amphibious assault ever launched. (Lead image above: Spitfires over Juno Beach, painting by Anthony Saunders.)

He must have felt pretty safe up there, far away from the battle shaping up below.

And then he was shot down by anti-aircraft fire!

Fortunately, he had time to bale out into the Channel. Like all fighter pilots, he was wearing his bright yellow Mae West life jacket. (Allied aircrew called their inflatable life preservers “Mae Wests,” partly from rhyming slang for “breasts” and partly because of the resemblance to the actress’s ample torso.)

Fortunately, he had time to bale out into the Channel. Like all fighter pilots, he was wearing his bright yellow Mae West life jacket. (Allied aircrew called their inflatable life preservers “Mae Wests,” partly from rhyming slang for “breasts” and partly because of the resemblance to the actress’s ample torso.)

Not long afterward, a landing craft full of soldiers pulled him out of the water, similar to this photograph. “I was the unhappiest man on that boat,” Arthur said.

Can’t you just imagine the poor guy huddled in the landing craft with a bunch of fighting men who were armed with the best weapons, trained to storm the beaches and engage in hand-to-hand combat with the enemy? In this photo(right) of American soldiers approaching Omaha Beach, you can see their camouflaged helmets, backpacks and rifles.

Can’t you just imagine the poor guy huddled in the landing craft with a bunch of fighting men who were armed with the best weapons, trained to storm the beaches and engage in hand-to-hand combat with the enemy? In this photo(right) of American soldiers approaching Omaha Beach, you can see their camouflaged helmets, backpacks and rifles.

Already soaking wet and freezing, Arthur was ordered off the boat along with everyone else. He had NO unit, NO commanding officer, NO training, and NO weapon – except for a service revolver, which all the pilots wore, in a clip stuck shut by salt water.

Here’s a photo of soldiers storming the beach.

Here’s a photo of soldiers storming the beach.

Arthur made no claims to bravery. “I headed for a concrete wall and hid behind it for three days.”

Troops that landed on the beach were well-equipped with such items as a raincoat, chocolate bars, extra socks and extra ammunition. Arthur had none of these things.

The beaches were a scene of pandemonium. By sunset on June 6, an incredible 175,000 British, American, Canadian and Free French troops had been carried across the English Channel to the Normandy Coast, in what was the largest amphibious landing the world had ever seen.

On the third day, Arthur was finally picked up by a landing craft evacuating some of the wounded men.

On the third day, Arthur was finally picked up by a landing craft evacuating some of the wounded men.

Halfway across the English Channel it was torpedoed and sunk! Once again, poor Arthur found himself in the drink!

For the second time in three days, he was pulled from the water by another vessel, this time heading back to England, and this time he safely reached Southampton.

He went straight to an officer and requested compassionate leave for being torpedoed.

“Torpedoed! Spitfire pilots don’t get torpedoed!” was the officer’s response.

After a heated discussion, Arthur got his leave and boarded a train for Wales, arriving in the middle of the night in a terrible rainstorm.

After walking a mile from the train station to his house, he knocked on the door and nobody answered. He threw pebbles against the window until his wife came downstairs and opened the door.

“But you’re dead!” she cried out.

“I’m not dead, but I’m wet! Let me in!”

It wasn’t until he got inside that she burst into tears. She had already received a telegram saying that he was missing in action.

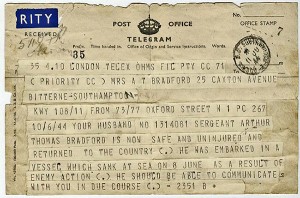

That first telegram is lost, but here is the second telegram informing her that her husband is safe. Of course, Arthur was home before the telegram arrived! It reads: “Your husband No. 1314081 Sergeant Arthur Thomas Bradford is now safe and uninjured and returned to the country. He was embarked in a vessel which sank at sea on 8 June as a result of enemy action. He should be able to communicate with you in due course.”

That first telegram is lost, but here is the second telegram informing her that her husband is safe. Of course, Arthur was home before the telegram arrived! It reads: “Your husband No. 1314081 Sergeant Arthur Thomas Bradford is now safe and uninjured and returned to the country. He was embarked in a vessel which sank at sea on 8 June as a result of enemy action. He should be able to communicate with you in due course.”

Arthur survived D-Day, but continued to lead a dangerous existence. He returned to his squadron at RAF Tangmere, serving with a mixed bunch of Brits and Canadians. They were attached to the army, strafing in front of the advance and taking reconnaissance photos. (The aerial cameras went off automatically whenever the guns fired).

After the Allies took back France, Arthur was stationed at Bayeaux in France, then Brussels in Belgium.

On New Year’s morning 1945 his station at Brussels was attacked unexpectedly by German fighters. “We’d had a do in the mess the night before, and nobody was interested in flying,” he said. They lost three fighters on the ground trying to get up but couldn’t.

According to Arthur, this was the Luftwaffe’s last gasp.

“By the time they finished, those fighters were out of ammo and almost out of fuel. We could see our guys already up in the air from other stations, just waiting for them over the Rhine. Not one of them made it back.”

Arthur continued to fly over Europe and ended up in Germany at a station called Stadthagen, near Aachen.

“We sometimes took over abandoned German airfields, but in this case the engineers had gone on ahead and made us a steel mesh runway. We were billeted in nearby homes abandoned by the Germans. I was in a schoolhouse.”

The long war finally ended, on May 8, 1945.

“One of our Canadian pilots had to return to Brussels for something. While he was there, the war ended. He wound his aircraft up to 25,000 feet to get the necessary range and then radioed the news to our station.

“Within an hour there was nothing left to drink in the mess!”

***

Arthur and his wife and son emigrated to Canada, where he worked as a teacher. His son Michael followed in his footsteps and became a school principal in Invermere, until his retirement. Arthur died in 1999.

(Yesterday) Saturday, June 6 – was the 71st Anniversary of D-Day – please take a moment to remember Arthur Bradford.

I like to think he will observe the celebrations from somewhere high above – perhaps zooming around in his Spitfire!

Thank you, Arthur Bradford, for your contribution to the freedom we enjoy today.

ABOUT ELINOR FLORENCE

Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

Elinor’s first historical novel was recently published by Dundurn Press in Toronto. Bird’s Eye View is the only novel ever written in which the protagonist is a Canadian woman in uniform during World War Two. The heroine Rose Jolliffe is an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs.

Elinor’s first historical novel was recently published by Dundurn Press in Toronto. Bird’s Eye View is the only novel ever written in which the protagonist is a Canadian woman in uniform during World War Two. The heroine Rose Jolliffe is an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs.

She spies on the enemy from the sky and makes several crucial discoveries. Lonely and homesick, she maintains contact with Canada through letters from the home front. The book is available through any bookstore including Lotus Books in Cranbrook, and also as an ebook from any digital book provider including Amazon, Kindle and Kobo. You can read more about the book by visiting Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com/birdseyeview