Home »

Fred Sutherland: The Last Canadian Dambuster

By Elinor Florence

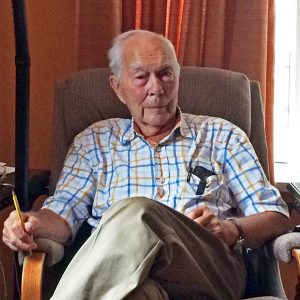

Fred Sutherland of Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, is now Canada’s last surviving Dambuster – one of only two men left in the world who participated in one of the most deadly, daring missions of the Second World War.

I grew up hearing about Fred Sutherland’s adventures, because he is married to my mother’s first cousin, the former Margaret Baker, so he is part of my extended family. But it was never the Dambuster story that was told by my mother – it was about those nerve-wracking months when Fred disappeared on a raid over Germany and the family didn’t know whether he was dead or alive – in many ways, a tale more harrowing than that of the Dambuster raid.

I visited Fred and Margaret recently at their cozy bungalow in Rocky Mountain House, Alberta. Their children live in other parts of the province, but 93-year-old Fred still drives and the couple manages very well in their own home, although Margaret has survived an ordeal with cancer.

While we enjoyed a glass of sherry, and caught up on family news, I asked Fred about his wartime experiences. In spite of being interviewed many times over the years, he graciously answered my questions.

The Early Years

Fred was born on February 26, 1923. His father Frederick Henry Sutherland was the local doctor in Peace River, Alberta – a small community 500 kilometres north of Edmonton. His mother Clara Caroline Richards was a nurse from Ontario who came to Peace River for work, and ended by marrying Fred’s father.

“It wasn’t until after she died that we discovered she was an aboriginal,” Fred said. “She was a Woodland Cree from Moose Factory, Ontario, who came south to stay with an aunt and take her nurse’s training. It was obviously a deep secret because she never said a word about it. I don’t know whether she was a full-blooded Cree, or a Metis. I don’t even know whether she told my father.”

The only son in his family, Fred grew up with two sisters, Kathleen and Alma. He dreamed of becoming a bush pilot in Canada’s wilderness. He had a girlfriend, pretty little Margaret Baker, who was the daughter of the local bank manager.

At the age of 18, before finishing high school, he joined the air force in July 1941.

Fred trains for “Operation Chastise”

Fred trained as an air gunner at Brandon, Manitoba, and arrived in England in spring 1942. He did his operational training at Royal Air Force Cottesmore in Rutland, England, where he “crewed up,” with Australian Les Knight as his pilot.

Their first operational unit was Royal Air Force Number 50 Squadron, at Skellingthorpe, Lincolnshire, where they began flying the Lancaster in September 1942.

It is a measure of their skill that this close-knit crew survived 25 trips over Europe. At the time, a full tour was 30 operations, and by March 1943 the seven-man crew was looking forward to completing their last five trips. Then they would have a respite before beginning their final tour of 20 additional trips.

His crew consisted of: their Australian pilot, Pilot Officer Les Knight; Australian wireless operator, Sergeant Robert Kellow; English flight engineer, Sergeant Raymond Grayston; English navigator, Flying Officer Sidney Hobday; English bomb aimer, Flying Officer Edward Johnson; Canadian rear gunner, Sergeant Harry O’Brien; and Canadian front gunner, Sergeant Fred Sutherland.

They were happy when they heard that two crews from their squadron were chosen to participate in a special top secret project – and in exchange, they would be granted the last five trips in their first tour.

“If you had made it through 25 trips, you were doing very well,” Fred recalled. “Our crew was considered one of the best. We volunteered for the special mission because we wanted to stay together.”

In total, 21 bomber crews were selected from RAF’s 5 Group, including Brits, Canadians, and other nationalities, to create a new squadron, RAF No. 617.

After the initial excitement, though, reality set in.

What was this special mission, and just how risky would it be?

“Everybody was curious. They told us not to try to figure it out, but amongst ourselves, we couldn’t help wondering.”

They didn’t know it yet, but they were about to become famous.

Scientist Barnes Wallis had developed the theoretical concept of a special “bouncing bomb” that would skip over the water like a skipping stone and lodge underwater against the wall of a dam, when it would explode.

But the bomb had to be dropped from an altitude of precisely 60 feet, at an air speed of precisely 390 kilometres per hour, and at a precisely-specified distance from the target.

This called for some fancy flying.

Without being told what the ultimate goal was, the crews went to work, dropping dummy bombs on targets. Then they progressed to spinning bombs filled with sand rather than explosives.

“Our crew thought we must be after the U-boat pens,” Fred said, referring to the dreaded German submarines. They still had no idea what their target might be.

During their preparations, Fred became acquainted with Guy Gibson (pictured below), the dashing 24-year-old heroic figure who led the Dambuster raid and is forever immortalized as a war hero.

“We were all impressed with Gibson’s flying,” Fred said. “Once he found this air strip in a forested area and side-slipped his Lancaster on to a perfect three-point landing on a very short runway.”

“We were all impressed with Gibson’s flying,” Fred said. “Once he found this air strip in a forested area and side-slipped his Lancaster on to a perfect three-point landing on a very short runway.”

Although Gibson was an excellent pilot, sometimes he chose not to fly himself. “Our pilot Les Knight was tops. He didn’t use bad language, and he didn’t drink. So Gibson would get our pilot to fly him down to London whenever he wanted to get lit up.” Apparently there were designated drivers, or pilots, in those days as well!

After the raid, Gibson was awarded the Victoria Cross and sent to the United States on a publicity tour, where he charmed adoring audiences. When he returned to Britain, he wrote a book about the raid. Sadly, this brilliant young man was shot down and killed in 1944.

Busting the Dams

The aircrews weren’t informed of their target until that very night – May 16, 1943. Fred remembered thinking that it was a suicide mission; he never expected to survive. “When you go into the target at 60 feet with all the lights on, you’ve had it.”

It was so secret that Fred didn’t hear the name of the mission until the briefing: Operation Chastise. The targets were three key dams: the Mohne, the Sorpe, and the Eder. The goal was to knock out hydroelectric power, and reduce the water supply needed by heavy industry in the Ruhr Valley.

Nineteen Lancasters took off that night, and eight were lost. The first formation attacked the Mohne Dam, and it was successfully breached. The Sorpe Dam was also attacked, but it held out.

The five aircraft still carrying bombs then turned toward the Eder Dam. The Eder Valley was covered by heavy fog, and the surrounding hills made the approach difficult. From his position as nose gunner, lying in a transparent bubble at the very front of the aircraft below the pilot’s cockpit, Fred must have felt particularly vulnerable.

The first aircraft made six unsuccessful runs. The second dropped a bomb that struck the top of the dam, but the aircraft itself was severely damaged in the blast.

Then Fred’s aircraft released the final bomb at just the precise moment – and it blew the dam wide open!

To this day, Fred credits his pilot for this feat. “Jumping over the hill and hitting the right speed and the right height was an act of genius.”

As you might imagine, there was much jubilation in the aircraft. “As soon as the dam was hit, the water was going everywhere,” Fred recalled. “There was a bridge down below the dam that just disappeared, just disintegrated. The force was terrific. We couldn’t believe it. We were just yattering away.”

In total, 53 of the 133 airmen who participated in the attack were killed – a casualty rate of 40 percent. Of those 30 Canadians, 14 were killed, one was taken prisoner, and 15 returned to base. Fred was one of the lucky 15 Canadians who returned safely.

Fred shot down; hides in Holland

After the Dambuster raid, RAF 617 Squadron was kept intact. Just four months later, on September 15, 1943, Fred’s crew set out on an almost identical raid on the Dortmund Emms Canal in Germany.

Their Lancaster was carrying a 12,000-pound bomb. It was a costly operation, with five of the eight aircraft failing to return. Fred’s was one of them.

While the low-level Lancaster was searching through the mist for the canal, it struck the tops of some trees. But their excellent pilot Les Knight managed to get the Lancaster across the border into Holland so all six of his crew could bale out before the aircraft crashed. Unfortunately Les Knight died in the crash. Five of the seven managed to evade capture, and one was taken prisoner by the Germans.

Fred thought he had been frightened during the Dambuster raid, but now he was terrified. “I’ve never been so scared in my life. I knew my best method of survival was to stay calm, and I kept telling myself: ‘Don’t panic! Keep your head!’”

He and his English navigator, Sidney Hobday, found each other after the crash. They remained in hiding for a day or two before being picked up by a Dutch civilian and taken to a camp deep in the woods, where about eight or 10 other men were hiding.

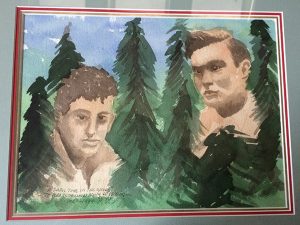

All were Dutchmen, evading the Nazi forced labour camps, except for one: a 17-year-old Jew named Ed Lessing. Ed spoke English, and the two boys became friends. Amazingly, they are still friends today. Ed Lessing lives in New York, but he has visited Fred in Rocky Mountain House. He even painted a picture of the two of them titled “A Dark Time in the Woods,” and gave it to Fred. It is a very cherished possession.

After a month hiding in the camp, the resistance fighters produced papers for Fred saying that he was a labourer on the Cherbourg Fortifications. They dressed him and Hobday in work clothes and put them on a train from Rotterdam to Paris.

“My seat was at the back of the car, beside the toilet,” Fred recalls. “People kept coming up to me and asking if the toilet was free, and I would either nod or shake my head since I couldn’t speak any Dutch. The train was full of Germans. It seemed that everyone I looked at was a German.”

The two Canadians made it to Paris, and were taken in by an elegant old lady named Madame Theresa Viellot. “Every night the three of us sat around and drank a bottle of wine.” They were there for another month.

The Long Walk to Freedom

Finally, it was time to evacuate the two men across the Spanish Pyrenees. After another train ride to Toulouse, they got into a truck with some American flyers.

“We went tearing along these mountain roads with a wild driver and came to a house at the foot of the mountains. There we were joined by some others. Our group consisted of 15 guys – French, Dutch, American, and British – accompanied by two Basque guides, for a total of 17. We walked for two days and two nights. At one point we got lost in the rain and the fog, trying to evade the German patrols.

“One American named Bill Woods was a photographer on a B-17. He only had cardboard shoes and he wore them out in a few hours, so I gave him mine. I had another pair that was too tight, so I put them on over my bare feet because I had no socks. I got blisters right away and by the time we reached our destination, my feet were a terrible mess.”

But they were safe at last, having traversed the famous Chemin de la Liberte route (The Freedom Trail). From Gibraltar, Fred was flown back to England in a Liberator, where he was finally able to send the precious telegram to his father.

“We used a special number to save on words. The number meant: ‘I am well. I am safe and sound.’”

Imagine the joyous hullabaloo in the Sutherland household back in Peace River! His parents immediately telephoned Margaret and told her the good news.

Fred’s Happy Homecoming

Fred’s flying career was over. Once an airman was rescued by the Resistance, he wasn’t allowed to fly again in case he was captured and forced to reveal the identities of his rescuers.

In December 1943 Fred sailed for home. He celebrated Christmas on board the ship, then took the train from Halifax to Edmonton. “When I got there, one of our Military Police stopped me and gave me heck for not having my coat buttoned up properly!”

But standing on the platform were his parents and Margaret, who had driven down from Peace River to meet him. Five hundred kilometres was a long journey in those days, but they couldn’t wait another minute.

To the surprise of his parents, Fred and Margaret announced their intention of being married immediately! It’s a good thing his parents were present, because Fred was still only 20-years-old. Margaret was born on November 21, 1922. Since she had just reached the majority age of 21, she was legally permitted to marry, but Fred needed his father’s permission to tie the knot!

The very next day, January 5, 1944, Fred and Margaret were married in an Anglican Church with his parents present.

Fred served as a gunnery instructor in Canada for the rest of the war. After the war he became a forestry inspector for the Government of Alberta and worked in Calgary, Edmonton, and Rocky Mountain House, where he retired.

His career meant that he spent much time in the wilderness, where he had some hair-raising encounters with bears. But Fred kept his head, just as he had done during the war.

Fred and Margaret raised three children. Joan is a Special Education teacher in Calgary, married to Hugh Norris. Thomas John is an equipment operator in Fort MacMurray, Alberta, married to Cathy Marriott. James Duncan Sutherland of Edmonton is a parts-man, married to Laurie Sutherland.

Fred and Margaret are still remarkably active. In February 2016 they drove their own car from Rocky Mountain House to Calgary and flew to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico for a holiday. Coincidentally, I was present on their return flight and it gave me the greatest pleasure to hear the Westjet pilot announce that we had a celebrated veteran on board, and to hear the passengers give him a round of well-deserved applause!

Lead image: Fred’s close-knit crew. Fred is seated at the centre rear.

Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

Elinor’s first historical novel was recently published by Dundurn Press in Toronto. Bird’s Eye View is the only novel ever written in which the protagonist is a Canadian woman in uniform during World War Two. The heroine Rose Jolliffe is an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. She spies on the enemy from the sky and makes several crucial discoveries. Lonely and homesick, she maintains contact with Canada through letters from the home front. The book is available through any bookstore including Lotus Books in Cranbrook, and also as an ebook from any digital book provider including Amazon, Kindle and Kobo. You can read more about the book by visiting Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com/birdseyeview