Home »

My Grandfather’s Narrow Escape

By Elinor Florence

It was exactly 100 years ago, in April 1918, that my grandfather’s life was saved on the battlefields of France during the First World War by his younger brother.

My maternal grandfather Charles Edward Light was a devoted family man and I knew him well, since he lived into my adulthood. Charlie was one of nine children. After finishing school he worked for his father Frederick Walter Light, the postmaster in Battleford, Saskatchewan. Here is the building we still refer to as “Grandpa’s Post Office,” where three generations of the Light family worked.

Sorting the mail was a dull occupation for a young man. One week after war was declared in September 1914, my 21-year-old grandfather was on his way to France, expecting to make short work of the Germans. “I’ll be home for Christmas!” he cheerfully told his anxious mother.

His sworn declaration, signed by every man who enlisted, indicates that the Canadians were overly optimistic. “I hereby engage and agree to serve in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force, and to be attached to any arm of the service therein, for the term of one year, or during the war now existing between Great Britain and German, should that war last longer than one year.”

Charlie was soon joined by his brother Jack, who lied about his age and enlisted on April 1, 1915. He had just turned 17. (Apparently this was not uncommon – if you looked full-grown and your parents didn’t object, the armed forces were happy to have you.)

When Charlie learned to his dismay that his little brother had joined up, he “claimed” him. That is, he requested the authorities that Jack join his unit as a family member. This was allowed in the first war, in the belief that it improved morale. But since multiple family members were often wiped out in a single battle, this practice was stopped in World War Two.

The two boys spent the rest of the war serving together in a famous Canadian cavalry unit, still based in Edmonton, called Lord Strathcona’s Horse.

My grandfather always said he joined the cavalry because he hated marching in the mud. However, he soon discovered one major drawback: your horse comes first. He spent many weary hours feeding and grooming his horse after a long day in the battlefield, while members of the infantry trooped off to bed.

Like most Canadians, his years there were fraught with peril. In 1916 he was shot in the leg, recovered and returned to the front.

The second, more serious wound almost cost him his life on April 1, 1918. In what was the last great cavalry charge of the First World War, Lord Strathcona’s Horse led by Lieutenant Flowerdew (who was killed and received the Victoria Cross posthumously in honour of his actions that day) recaptured a section called Moreuil Wood and the smaller area called Rifle Wood to the north.

The lead image above is a painting of that famous battle, called Charge of Flowerdew’s Squadron, by Alfred Munnings, the official war artist for the Canadian Cavalry.

In the nearby heavily-forested Rifle Wood, the cavalry dismounted and engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat with fixed bayonets. A shell exploded behind Charlie and fragments of shrapnel pierced his lower back and kidney.

Now here’s where brother Jack comes in.

According to Jack, he lost sight of his older brother in the battle and found him unconscious, lying on the ground in a huge pool of blood. Frantically, he ran through the gunsmoke and the exploding shells in search of the medics.

When he found them lifting another wounded soldier onto a stretcher, he screamed: “My brother is wounded! Over here! Come and take my brother! He’s dying!” The medics refused, since they already had their man.

At this point Jack lost his head and drew his service revolver from his holster. Training it on the two medics, he screamed: “You come and take my brother now, or by God I’ll blow your heads off!”

The terrified medics abandoned their hapless victim and hurried off at gunpoint to find my grandfather. They loaded him onto the stretcher and bore him away. He was transported to a field hospital and then shipped back to a hospital in England where he spent three long months recovering from his terrible wounds.

So did this really happen? The story was told often by Jack in the years that followed. Since Charlie was unconscious throughout, he couldn’t comment. Several of my relatives are skeptical that you could get away with brandishing a revolver at the medical corps, even in the heat of battle.

But I’m convinced the story is true. The bond between the brothers was a powerful one. And I expect the medics were far too busy saving lives to worry about one soldier more or less, especially when they saw the sorry state of my grandfather.

Both brothers survived the war. Jack escaped unscathed, and Charlie recovered from his terrible wounds and returned to the front once again, where he remained until the war ended in November 1918.

Charlie returned to work in the post office in Battleford (an occupation that now didn’t seem quite so boring), and eventually became the postmaster himself, a position he held until his retirement.

He also married his boyhood sweetheart Veronica Scott, who had written to him throughout the long war years, beginning her letters: “Dear old pal!”

They inherited the handsome house from Charlie’s parents that stood on the edge of Battleford. There they raised three sons and two daughters, one of whom was my mother June. It was sold out of the family but still stands today.

After the war, Jack left Battleford and pursued a successful career with the Alberta Provincial Police. He, too, married and had three sons. Many of the Light family souvenirs, including Charlie’s uniform, can be seen in the museum created by Frederick, the youngest of the three brothers.

The Fred Light Museum now belongs to the Town of Battleford. It’s well worth a visit.

I have three precious mementoes from Charlie’s war years.

Below is his shaving mirror. It’s a tarnished piece of stainless steel in a leather case which, when polished, could hang on a nearby tree branch and reflect my grandfather’s handsome face.

It also had another purpose. Kept in the left breast pocket, it protected his vulnerable young heart from a bullet.

It also had another purpose. Kept in the left breast pocket, it protected his vulnerable young heart from a bullet.

Below right are his field glasses. The magnification isn’t very good. I’ve tried looking through them, and wonder how anybody ever saw anything, let alone a German soldier in a trench.

Finally, at the bottom of the story is my most precious souvenir.

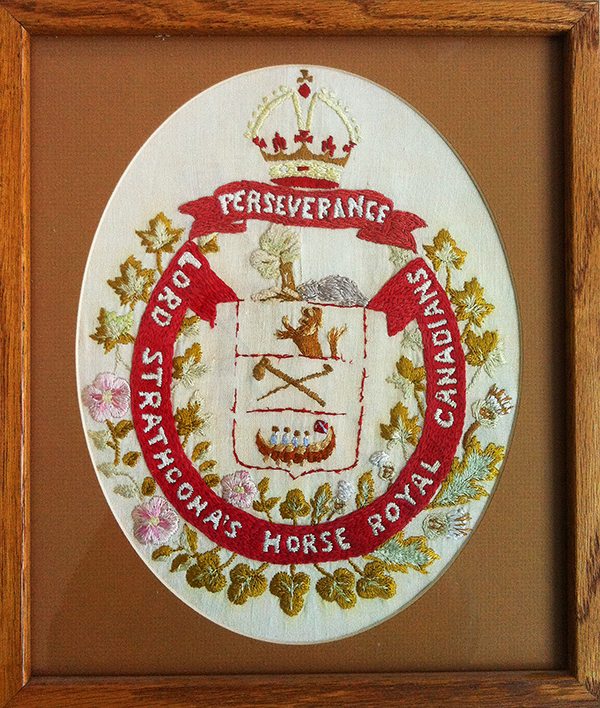

While spending the long and weary weeks recovering in an English hospital, Charlie took up needlework. The soothing repetition helped stitch together his mind as well as his body. He chose a subject dear to his heart: the Lord Strathcona’s Horse regimental crest.

The crest is crammed with images. It bears the motto “Perseverance,” along with a beaver chewing a tree, the British lion, a hammer and nail, and four men in a canoe, all surrounded by a wreath of English roses, Scottish thistles and Irish shamrocks.

The crest is crammed with images. It bears the motto “Perseverance,” along with a beaver chewing a tree, the British lion, a hammer and nail, and four men in a canoe, all surrounded by a wreath of English roses, Scottish thistles and Irish shamrocks.

One hundred years after the wound that nearly cost him his life, Charlie’s wartime souvenir hangs on my wall, a permanent reminder of a badly-wounded young man who found solace in his squadron’s motto: “Perseverance.”

– Elinor Florence lives in Invermere. Her first novel Bird’s Eye View, about a Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the air force in World War Two and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs, is a Canadian bestseller. Her new novel Wildwood tells the story of a single mother from the big city who inherits an abandoned off-the-grid farm in northern Alberta. Both books are available at Coles and Lotus Books in Cranbrook. For more information about Elinor and her books: www.elinorflorence.com .