Home »

Lou Marr: farm girl turned RCAF photographer

By Elinor Florence

Lou Marr called herself “the turnip that fell off the back of the truck” when she joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, Women’s Division and became a photographer. It was hard work, but it also allowed her to fly right alongside the men in training. For this Alberta farm girl, it was the thrill of a lifetime.

Lou Marr called herself “the turnip that fell off the back of the truck” when she joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, Women’s Division and became a photographer. It was hard work, but it also allowed her to fly right alongside the men in training. For this Alberta farm girl, it was the thrill of a lifetime.

Airwomen who worked in the field of photography are a special interest of mine, so I’m happy that I was able to interview Lou Marr in Windermere, British Columbia several years before she died in 2008. She lived alone in her small house beside the highway, on a piece of property now known as “Marr’s Landing,” surrounded by her collection of Cabbage Patch dolls, wearing little outfits sewn by Lou herself.

The female veterans I know have one thing in common: they are strong-minded, independent women. And Lou was certainly no exception! She had a real sense of humour and I don’t think I have ever laughed so often during an interview. Lou told many amusing anecdotes from her wartime days, some of which wound up in my wartime novel, Bird’s Eye View.

The Early Years

Lula Pound grew up on a farm without electricity or plumbing near Daysland, Alberta. When her father died, her mother continued to run the farm with the help of Lou and her younger brother, who was unable to enlist because of his poor eyesight.

Lou finished high school and 10 days later, on July 8, 1942, she married Thomas Marr, a young man from Manitoba who worked as their hired man. Tom had already joined the Canadian Army and was on his way overseas.

Tom was in uniform; Lou wore a sheer blue dress with lace peeping through the bodice. Her new husband kissed her goodbye and left in the pouring rain. She didn’t see him again for four years.

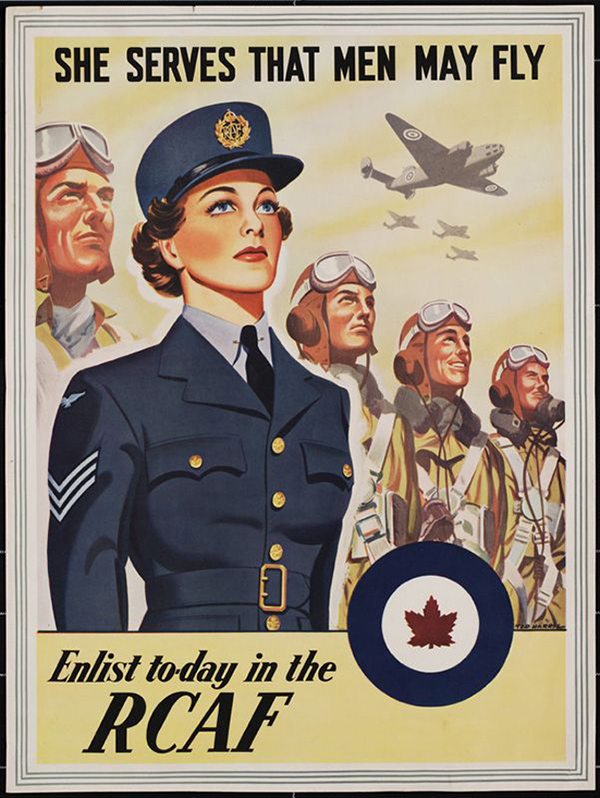

Most of the boys from her high school had already joined up and left town. Lou was burning with patriotism to serve her country and fight for Canada. She listened to the family’s “little tin radio” as it described the great battles taking place on the other side of the world. Everywhere she saw recruiting posters like this one.

But she didn’t want to join the forces without her husband’s permission, so she wrote to Tom overseas and asked if she could join up.

His answer was: “Only the air force.” Being in the army himself, he took a dim view of the behaviour of “army girls.”

Lou Joins the Royal Canadian Air Force

Lou’s mother drove her to Edmonton and she enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force, Women’s Division, in April 1943. Shortly afterward, she left on a train with a group of other young women, destined for basic training in Rockcliffe, just outside Ottawa. “The train was filled with hundreds of inebriated Australians, all bragging about how many sheep they had back home,” she recalled.

When they arrived, some girls had to be treated for “cooties” – head lice they had picked up on the train. Lou also remembered that all the girls had a urine test for pregnancy, and some were shipped home immediately when it was found they were pregnant.

The barracks in Rockcliffe were far from luxurious. Lou slept in a double metal bunk, scrubbed the wooden floor on her hands and knees, and saw cockroaches for the first time – in the mess hall!

Lou’s favourite occupation was marching. She said it was grand when she marched down one of Ottawa’s main streets behind a pipe band, encouraging people to buy War Bonds. “I get shivers when I hear the pipes even today,” she said.

Under their uniforms, the girls wore garter belts and black cotton stockings. One day while on drill, Lou’s garter belt gave way and she stood in great anxiety while her stockings slowly slid down towards her ankles. Thankfully the women were dismissed before her officer noticed!

The stockings caused another problem, too – when Lou’s feet perspired, the black dye ran. The dye got into an open blister and caused blood poisoning. Lou thought she was too “tough” to go to the doctor.

Several days later her sergeant ordered the girls to fall out and take a break on the grass, telling them they could remove their shoes if they liked. Lou couldn’t even get her shoe off because her foot was so badly swollen. She was sent off to the medical clinic immediately.

Lou becomes handy with a camera

After six weeks of basic training, the women received their assignments. Lou was first assigned to code-and-cipher, but she really wanted to study photography, and happily she was given permission to take the eleven-week photography training course. This was one of the more difficult trades, and required a great deal of study.

Lou had taken photographs on her old Brownie camera. Now she learned how to take apart and assemble a camera, how to develop and print photographs, and how to piece together aerial maps.

Her training included flights with an instructor and a pilot, “some 18-year-old kid who was just learning to fly himself,” according to Lou. Wearing one-piece coveralls, armed with a camera and a heavy parachute on her back that hung down to her knees, she would lie face-down on the floor of the airplane over a piece of Plexiglas and miles of open air, taking photos of the terrain below. Back at base, she learned to print four-inch by four-inch photos and overlap them in a diagonal pattern to form an entire aerial map.

Her training included flights with an instructor and a pilot, “some 18-year-old kid who was just learning to fly himself,” according to Lou. Wearing one-piece coveralls, armed with a camera and a heavy parachute on her back that hung down to her knees, she would lie face-down on the floor of the airplane over a piece of Plexiglas and miles of open air, taking photos of the terrain below. Back at base, she learned to print four-inch by four-inch photos and overlap them in a diagonal pattern to form an entire aerial map.

Another duty was to photograph any piece of equipment that had broken or was otherwise defective – a cracked strut on an airplane, for example – to send to the manufacturer so the fault could be corrected.

“It was so hot and humid in Ottawa that we used to strip down and do our darkroom work in our bras and panties,” she recalled. “Of course, no one was allowed in the darkroom when the red light was on, so we figured we were pretty safe.” (That fascinating tidbit is one of the reasons I love hearing first-hand experiences, and this one definitely made it into my book.)

The Star Weekly was a newsmagazine published by the Toronto Star, and it featured this article about the camerawomen of the Royal Canadian Air Force.

Speaking of red lights, one weekend Lou travelled to Montreal for the first time with a couple of girlfriends. There someone referred to the city’s red light district. “What’s that?” she asked innocently. In later years, she laughed at the memory. “Talk about people being so naive they were like turnips that fell off the back of a truck. That was me!”

For a new experience, the women also daringly ventured across the border between Ottawa and Hull, Quebec. “We used to ‘howl like hell in Hull,’ as the old saying goes,” Lou laughed.

Not all her memories were happy ones. As was typical in those years when young men were just learning to fly, sometimes there were fatal accidents on the base. Rockcliffe looked down onto the airfield, and one day Lou saw a Mosquito land and burst into flames. “The pilot didn’t have a chance,” she said sadly.

Lou posted to an Air Training Base in Dauphin, Manitoba

At the end of three months, Lou passed her exams and became a full-fledged photographer. Of course, her dream – like virtually every Canadian woman in uniform – was to be posted overseas. “I can remember sitting on the curb with a young guy, both of us crying,” she said. “I was crying my eyes out because I didn’t get an overseas posting; he was crying because he did!”

Lou requested a posting to Western Canada instead. She wanted to return to Alberta, but ended up in Dauphin, Manitoba, a British Commonwealth Air Training Base about 25 kilometres outside town. On the base were 200 women and 2,000 men.

Since the base was so far from town, the airmen and airwomen didn’t go into Dauphin often, but there were regular dances on the base, and plenty of social activities. Lou hung around with crowds of young airmen, but she promised me there was no hanky-panky.

Some evenings they hung heavy curtains over the windows so anyone passing by couldn’t see the party going on inside. Dauphin was the only wet canteen (one that serves alcohol) in the whole of Western Command. “Unfortunately, I didn’t drink,” Lou said.

She didn’t smoke, either, unlike most others in the armed forces. Cigarettes were available then at $1 per 200, to send overseas to the servicemen. Lou sent Tom almost everything he asked for, including a guitar.

“He told me when he got back he must have been the only person in England on VE Day who had a jar of pickled onions from home!”

Of course, the WDs felt superior to the other two female branches of the forces. “We walked around like we were somebody,” Lou recalled. “The Wrens were sissies, and the army girls were bad girls, but we were the cream of the crop!”

Lou looks uncharacteristically serious in this studio portrait of herself.

Lou was discharged in 1944 when the war began to wind down. She would dearly have loved to stay in the services, but married women were the first to go. She was discharged at the Currie Barracks in Calgary, and returned to the farm to wait for Tom, who arrived back in Canada in 1945.

After the War

Tom and Lou moved around Alberta and British Columbia before settling near Windermere. Tom worked at Lake’s Service Station, and Lou was employed as a practical nurse at the local hospital.

They built their own house in Windermere and raised four children, one girl and three boys. Daughter Patty Marr has two children, Melissa Marr and Christian Jones. Andy Marr and his wife Hiroko have one daughter, Leiko Marr. Kerry Marr, who is deceased, had three children: Cheyenne, Nicholas and Dimitri. Doug Marr has two children: Carissa Marr Hicks, and Brandon Marr.

Tom died in 1995, and Lou lived alone in the house in Windermere until her death in 2008. Her Cabbage Patch dolls were sold and the proceeds donated to charity. Lou Marr continued to pursue her passion for photography her whole life.

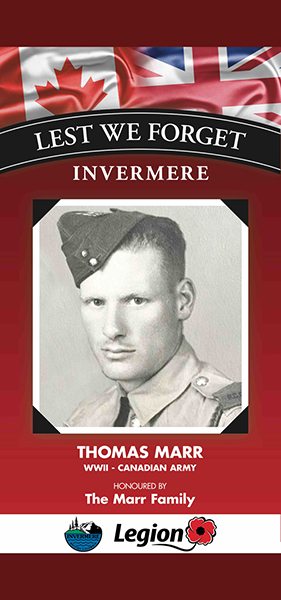

This year, the Marr siblings honoured both of their parents through the Royal Canadian Legion’s new Honour Our Veterans program in Invermere, by sponsoring a double-sided hanging banner bearing their portraits. Seventy-four local veterans are featured on the Invermere banners, which will hang each year from the first week of October until the last week of November.

Lou Marr’s portrait appears on one side of the banner. She was one of 50,000 Canadian women who served in uniform during the Second World War.

And her husband Tom Marr appears on the other side.

Lou Marr’s story is excerpted from Elinor Florence’s anthology of veteran interviews titled My Favourite Veterans: True Stories From World War Two’s Hometown Heroes. It’s available from Lotus Books in Cranbrook, Lambert-Kipp Pharmacy in Invermere, or directly from the author by calling 250-342-1621. For more info, visit Elinor’s website: www.elinorflorence.com.

– Career journalist and bestselling author Elinor Florence of Invermere has written two wartime books. Her novel Bird’s Eye View tells the story of an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. My Favourite Veterans is a non-fiction collection of interviews whose stories appeared previously on e-KNOW, including Cranbrook’s own Bud Abbott.

Elinor’s new novel Wildwood, about pioneer life in the Peace River, Alberta region, will appear in February 2018. It is available for pre-order now at a reduced price on Amazon. For more information about all three books, visit Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com or call her at 250-342-1621.