Home »

East Kootenay lumberjacks went to war

By Elinor Florence

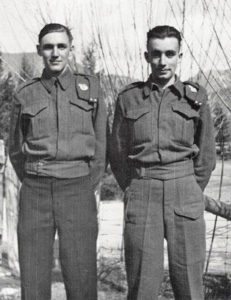

Thousands of lumberjacks, members of the Canadian Forestry Corps, logged the forests of Scotland during the Second World War to produce desperately needed lumber for the war effort. Among the loggers were Carl and Jack Jones (pictured right), two brothers from Invermere, British Columbia.

Thousands of lumberjacks, members of the Canadian Forestry Corps, logged the forests of Scotland during the Second World War to produce desperately needed lumber for the war effort. Among the loggers were Carl and Jack Jones (pictured right), two brothers from Invermere, British Columbia.

During the Second World War, it was estimated that every soldier needed the equivalent of five trees: one for living quarters and recreation; one for crates to ship food, ammunition, and other equipment; and three for explosives, ships and factories. Many of them, sadly, needed wood for their own coffins.

The Canadian Forestry Corps, a military unit in the Canadian Army, was created during the First World War. At first, the plan was to ship Canadian trees overseas, but with limited space aboard merchant ships, instead our skilled lumberjacks were sent to harvest the vast forests of Scotland instead.

The same demand for wood arose during the Second World War, and in May 1940 the Canadian Forestry Corps was reinstated. Once again, thousands of volunteers came forward, many of them veterans of the First World War.

Thirty companies were drawn from all regions of Canada including Quebec. Altogether about 7,000 men were deployed to Scotland. Among them were the Jones brothers from Invermere.

Thirty companies were drawn from all regions of Canada including Quebec. Altogether about 7,000 men were deployed to Scotland. Among them were the Jones brothers from Invermere.

Frank Jones and his wife Dorothy Pitts were the children of early settlers from England, who arrived in the Columbia Valley in the early 1900s.

They had three children: John (Jack) Alfred Jones, born July 11, 1919; Carlton Frank (Carl) born on November 30, 1921; and Alice Emily, born on October 8, 1924. This photo shows the young couple with their firstborn son Jack.

The children grew up amidst the spectacular natural surroundings of the Rocky Mountains. This photo shows the three children with their dog, Peter.

The children grew up amidst the spectacular natural surroundings of the Rocky Mountains. This photo shows the three children with their dog, Peter.

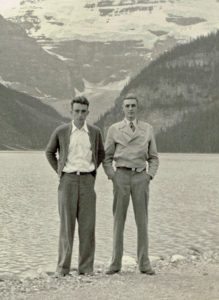

The two boys enlisted on September 12, 1940 when Jack was 21 years old and Carl was just 18 years old. After Carl finished Grade 10, he began working as a bank teller at a local bank, but clearly longed to join his brother in the great adventure overseas. Here’s a photo of the two boys standing in front of the famed Lake Louise.

Like most towns across Canada, there was tremendous local support for the men and women who enlisted. When Carl left home, the whole village gave him a party.

They weren’t alone in their quest. Other local men who volunteered for the Canadian Forestry Corps were: Alexander (Sandy) Dobbie, Alex (Jigger) Johnston, Charlie Pickard, Roy Smith, Andrew Staberg, and Archie Thompson. Lucien Jimmie, Isadore Michel, and Matty Sam were from nearby reserves. The lead photo above shows two local friends, Roy Smith, left, and Carl Jones.

They weren’t alone in their quest. Other local men who volunteered for the Canadian Forestry Corps were: Alexander (Sandy) Dobbie, Alex (Jigger) Johnston, Charlie Pickard, Roy Smith, Andrew Staberg, and Archie Thompson. Lucien Jimmie, Isadore Michel, and Matty Sam were from nearby reserves. The lead photo above shows two local friends, Roy Smith, left, and Carl Jones.

During the First World War, the foresters had not been trained for combat. This time around, because of the very real threat of Germany invading the United Kingdom, the Canadians were considered combatant troops and received military training.

The Jones boys received their equipment and some initial training near Victoria and then boarded the train to Valcartier, Quebec where they spent another six months training before shipping overseas to Scotland on April 5, 1941. Below is their badge, featuring the maple leaf, the Canadian beaver, and two crossed axes.

They sailed on the MS Batory (Motor Ship Batory was an ocean liner belonging to the Polish merchant fleet that acted as a troop transport ship) and landed at Gourock near Glasgow, Scotland. They took the train to Beauly, a village not far from Inverness in northern Scotland. From here they were dispersed among the vast Scottish estates to cut the forests owned by the nobility, including the Royal Estate at Balmoral.

Both Jones brothers were stationed near the town of Kiltarlity. They were members of No. 18 Company, Canadian Forestry Corps, District 5. Their camp was called Lovat No. 1, named after the enormous 19,500-acre Lovat Estate.

Both Jones brothers were stationed near the town of Kiltarlity. They were members of No. 18 Company, Canadian Forestry Corps, District 5. Their camp was called Lovat No. 1, named after the enormous 19,500-acre Lovat Estate.

Lord and Lady Lovat lived in nearby Beaufort Castle. The lord himself was a British commando and decorated hero during the Second World War. Below is a photo of Beaufort Castle today; it passed out of the hands of the Lovat family in 1995.

Each of the 30 Canadian companies had about 200 men. They worked in two sections, one cutting in the bush and bringing out the timber, and the other sawing it into lumber at the company mill.

The men brought with them the most up-to-date logging equipment available in Canada, including caterpillar tractors, lorries, sulkies (two-wheeled contraptions with rubber tires to drag logs out of the bush) and winches for high-lead logging.

The men brought with them the most up-to-date logging equipment available in Canada, including caterpillar tractors, lorries, sulkies (two-wheeled contraptions with rubber tires to drag logs out of the bush) and winches for high-lead logging.

However, axes and crosscut handsaws continued to be their stock tools of the trade.

Scots pine, spruce and larch were most commonly harvested. The Scottish forest was characterized as “medium timber,” smaller than the huge Douglas firs of the B.C. forests, but heavier than the average woods found in the other provinces. This photo shows the size of the logs commonly harvested.

The men were pleased by the relative openness of the cultivated Scottish forest, in contrast to the tangled undergrowth of most Canadian bush. Nevertheless, pressure was applied to Canadian fallers to cut trees close to the ground in the Scottish fashion, rather than higher up, which left unsightly stump-fields. Pictured here on the left is G. F. Dick from Port Arthur, Ontario; on the right is Zachary Birdstone from Cranbrook.

Since they were working even farther north than in most Canadian logging operations, the winter days were short and dark. The work was hard, and the damp, chilly climate with mixed rain and snow was even more challenging than the cold Canadian winters. The men’s hands were often cut up by handling wet lumber in raw weather.

Since they were working even farther north than in most Canadian logging operations, the winter days were short and dark. The work was hard, and the damp, chilly climate with mixed rain and snow was even more challenging than the cold Canadian winters. The men’s hands were often cut up by handling wet lumber in raw weather.

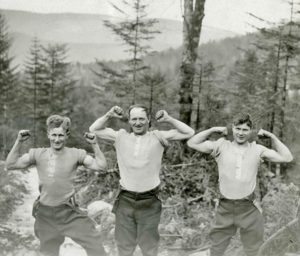

Thankfully these men lived up to their reputation as stalwart Canadian lumberjacks. Below three unnamed men show off their muscles in this photo from the Canadian War Museum.

Although the climate was chilly, they enjoyed a warm welcome from the Scottish people. Many lifelong friendships and marriages were made. The forestry corps was also kind to their neighbours. They sold scrap wood from the sawmills to the public for fuel, and at times some of it mysteriously fell from the trucks to land beside homes in financial need.

A notable tribute was paid by Laura Lady Lovat, who stated: “You Canadians may be cutting the Scots firs of the Highlands, but in Highland hearts you are planting something far more lasting.”

A notable tribute was paid by Laura Lady Lovat, who stated: “You Canadians may be cutting the Scots firs of the Highlands, but in Highland hearts you are planting something far more lasting.”

There were weekly dances and church parades. Films were shown in the mess hall, and travelling concert troupes made frequent visits. Several important personages visited the Canadians to thank the lumberjacks, including the Queen herself.

Known as “the Sawdust Fusiliers,” the Canadian men also continued their military training on Saturdays after their week’s work in the woods, preparing to protect the local residents and neighbouring airfields in case of attack. This included rifle range practice, training with bayonets, and tactical exercises with other military units.

Below, a young Carl Jones is looking very proud of himself in his uniform: khaki shirt and woollen trousers with two external pockets – one on the upper right thigh, designed to hold a field dressing; and a larger pocket on the left thigh, commonly called a map pocket. Usually a khaki beret was worn, but here he is sporting his Glengarry beret, the traditional headwear of the Scottish regiments in the Canadian Army.

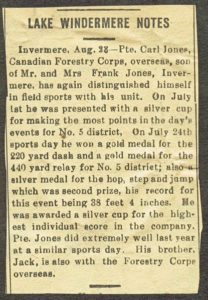

The men engaged in plenty of sports, track and field and games. They even brought the previously unknown game of softball to the Scottish highlands. Carl Jones had always been a keen athlete, and he enjoyed competing in various events.

The men engaged in plenty of sports, track and field and games. They even brought the previously unknown game of softball to the Scottish highlands. Carl Jones had always been a keen athlete, and he enjoyed competing in various events.

After the successful invasion of Normandy in June 1944, the demand for timber to rebuild bombed bridges and roads was high.

Of the 30 forestry companies, 10 returned to Canada to continue cutting wood to meet the fuel shortage in this country. Another ten companies went to the continent, and the remainder stayed in Scotland to continue their work.

Carl Jones landed in France on July 30, 1944 and later served in Belgium and then Germany before the war ended. The lumberjacks cleared the German forests in preparation for the Canadian Army’s advance, although many trees were unusable since they had been splintered by shells or had metal shrapnel lodged in them.

Germany surrendered in May 1945, but it wasn’t until September that the Canadian Forestry Corps was officially disbanded. Many of their members had been away from home for four or five years. The Canadian Forestry Corps had cleared about 230,000 forest acres in Scotland during their stay.

Germany surrendered in May 1945, but it wasn’t until September that the Canadian Forestry Corps was officially disbanded. Many of their members had been away from home for four or five years. The Canadian Forestry Corps had cleared about 230,000 forest acres in Scotland during their stay.

After the War

Both Carl and Jack returned to their beloved Rocky Mountains in November 1945 and were greeted by a huge homecoming celebration in the town of Invermere.

Like so many other Canadians, the brothers were eager to get back to the great outdoors. A note on Carl’s discharge papers read: “This man has had a good education and is very intelligent and alert, and is capable of doing bigger things than labouring in the bush, which is his present intention. However, he wishes to remain in his home district and has no desire to return to his former employment in a bank, so logging is the only field open to him.”

The brothers purchased a truck and became haulers, working in the lumber and mining industry. They even trucked Christmas trees as far as Idaho.

The brothers purchased a truck and became haulers, working in the lumber and mining industry. They even trucked Christmas trees as far as Idaho.

Carl married his wife Marion Cleland in 1946. Below are Carl and Marion on their wedding day, with best man Jack Jones on the left; and Marion’s sister Allison Cleland on the right.

Although Carl also worked as a mechanic, his greatest love was ranching. He and Marion bought a ranch overlooking Lake Windermere where they built their own log house and raised Charolais cattle, pigs, and chickens, along with a huge vegetable garden. They had three children: Sandra, Suzanne and Jim.

Jack also was an avid outdoorsman who spent most of his career in the guiding business. He had married a Scottish girl, Margaret Green, who came to Canada as a war bride. But Margaret was terribly homesick and she returned to Scotland with their little daughter Veronica, who died in a bicycle accident at the age of four.

Later Jack married Honny Wenger in Invermere and had four children: stepdaughter Sonja, Kathi, Frank and Wayne. After Honny passed away, he married Mildred Jones.

Later Jack married Honny Wenger in Invermere and had four children: stepdaughter Sonja, Kathi, Frank and Wayne. After Honny passed away, he married Mildred Jones.

While her two older brothers were overseas, their little sister Alice joined The Canadian Women’s Army Corps at the age of 18, serving in Prince Rupert, Vancouver and Calgary before marrying RCAF airman Gestur Palmason in 1944. She and Gestur had three daughters: Diane, Sherie, and Gloria. After Gestur passed away, she married Harold Knight. Alice died on March 1, 2008.

Carl continued his love of sports, both as a participant and a coach. He volunteered with the Legion sports program and coached children in track and field. He was also an avid hockey fan and coached hockey teams.

After he retired, Carl’s favourite occupation was fishing with his best friend Jim Ashworth. Jim was a former pilot with the Royal Canadian Air Force who is still living in Invermere. You can read his story here.

Carl died on March 16, 1995 and Jack died on October 11, 2007. Both Carl and Jack left a legacy of local descendants. There are now six generations of Jones in Canada who descended from the original British pioneers, and many of them still reside in this area.

Much of the information here was gathered by Sandi Jones of Invermere, eldest daughter of Carl Jones, who put together a photo book for her family as a permanent record of her father’s adventures abroad.

Much of the information here was gathered by Sandi Jones of Invermere, eldest daughter of Carl Jones, who put together a photo book for her family as a permanent record of her father’s adventures abroad.

She made the trip to Scotland in 2014 to see where her father had spent his wartime years, about five kilometres from the village of Kiltarlity. Because the camp structures were built from wood, little remains now of Camp 10 except a rusty water tower and some crumbling foundations.

“It was a powerful experience, with tears, and I loved the idea of being on the same land where Dad lived and worked,” she said.

– Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

– Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

Elinor’s first historical novel was recently published by Dundurn Press in Toronto. Bird’s Eye View is the only novel ever written in which the protagonist is a Canadian woman in uniform during World War Two. The heroine Rose Jolliffe is an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. She spies on the enemy from the sky and makes several crucial discoveries. Lonely and homesick, she maintains contact with Canada through letters from the home front.

The book is available through any bookstore including Lotus Books in Cranbrook, and also as an ebook from any digital book provider including Amazon, Kindle and Kobo. You can read more about the book by visiting Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com/birdseyeview.