Home »

Seeing the Unseen: Searching for Tailed Frogs

In a case of CSI meets wildlife biology, ecologists can now identify a species’ presence without actually observing it. Call it seeing the unseen.

In a case of CSI meets wildlife biology, ecologists can now identify a species’ presence without actually observing it. Call it seeing the unseen.

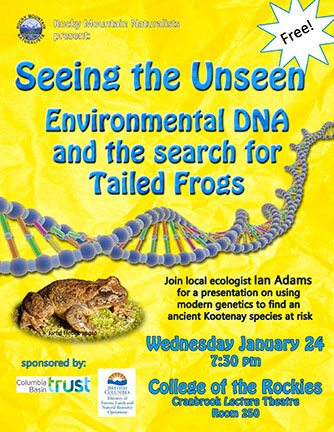

On Wednesday January 24 at 7:30 p.m., a free presentation at College of the Rockies in Cranbrook will demonstrate how scientists use eDNA to help identify a notoriously hard-to-find species.

The Rocky Mountain Tailed Frog is one of the lesser-known wildlife species in the Kootenays. A remarkably unique amphibian, tailed frogs have an amazing life history that set it quite apart from other frogs. When people think of frogs, most imagine wetland ponds and lily pads. Tailed frogs want nothing of such a staid and lentic lifestyle. Typical of many human residents of the Kootenays, tailed frogs are drawn to mountains, fast water and old forests. Their home is centred on upper elevation streams running through riparian forests that offer deep shade and cool waters.

Tailed frogs are unique. They are among the oldest known frogs, having branched off the common “frog” ancestor over 250 million years ago, just as dinosaurs were first appearing. Their closest relatives today are a few species of frog found only in New Zealand. It’s likely been a while since they had a reunion.

Today’s Rocky Mountain Tailed Frog has been isolated for at least three million years and survived the Pleistocene ice ages in glacial refugia not far south of the Kootenays. They are limited to the mountainous inland northwest and were previously known from only two drainages in Canada: west-side tributaries of the Flathead River and the Yahk watershed south of Moyie.

Recent evidence suggested tailed frogs may occur a bit more broadly than previously thought in the Kootenays. Using newly available genetic methods, local biologist Ian Adams teamed up with Jared Hobbs of Hemmera Envirochem to search for tailed frogs. They’ve had some surprising findings.

Their search was a rapid survey of streams looking for the frogs’ DNA. Environmental DNA, or eDNA, is an emerging ecological technique where genetic material from shed cells is captured in a water sample and preserved through filtering and drying. It can be used to identify everything from rock snot to bull trout – anything with DNA. A genetics laboratory then attempts to amplify (reproduce) short gene sequences known only from the target species. If the DNA sequence shows up in measureable quantities, the target species – in this case Rocky Mountain Tailed Frogs – is confirmed to be present.

Rocky Mountain Tailed Frogs are a species-at-risk and face several conservation challenges. Their unique biology leaves them susceptible to a variety of environmental stresses relating mostly to water quality and quantity in their stream habitat. The predicted climate change scenarios for the Columbia Basin – earlier, faster spring freshets followed by hotter, drier summers with more frequent and severe wildfires – are not going to be beneficial.

To learn more about the Rocky Mountain Tailed Frog and eDNA methods, join Adams for a free presentation Wednesday, January 24 on using modern genetics to find an ancient Kootenay species at risk.

Lead image: A Rocky Mountain Tailed Frog. Photo by Jared Hobbs

Submitted