Home »

Do not deny yourself reading Cormac McCarthy

Book Review

By Derryll White

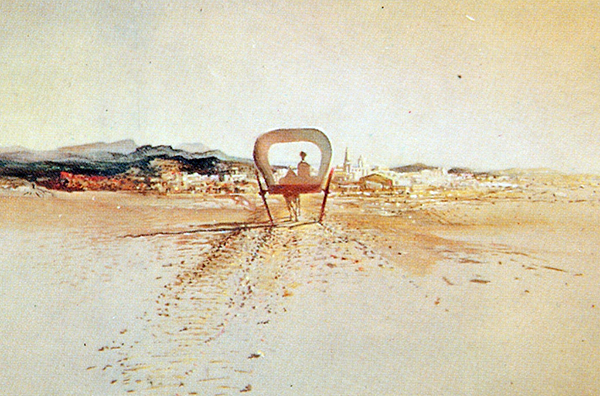

Cormac McCarthy (1985). Blood Meridian: Or the Evening Redness in the West.

Cormac McCarthy (1985). Blood Meridian: Or the Evening Redness in the West.

“Moral law is an invention of mankind for the disenfranchisement of the powerful in favor of the weak.” Cormac McCarthy

Should you read this book? If you are a writer yourself looking for a way into the craft, a measure of greatness, definitely. If you are a writer of meager talent and larger ego, probably not. More to the point, if you are a reader who luxuriates in the spellbinding power of the very best of writers – Faulkner, Borges, Steinbeck, Neruda, Galeano – then you should not deny yourself. You will be well served for now and for a long time to come.

The group of scalp hunters central to this novel made a communal soul joined together out of a shared hardship and purpose, a bleak soul fueled by the need to eradicate the Apache people. There is no right or wrong in this conjoining as the author allows no speculation. He lays out what is for him the debased fact of humanity’s innate nature. God does not mean to interfere in the degeneration of mankind. God leaves us to our own course.

This man, this writer with his consummate command of language and unhindered demand to know the true place the American West was in the 1850s, leaves me happily talking to myself and taking apart the natural world not so as to know things specifically but so as to try to understand how I fit in a world so exquisitely circumscribed.

Always in this novel there is the immaculate focus on the power of the word, of the acceptance of power other than nature, of naming.

“Like beings provoked out of the absolute rock and set nameless and at no remove from their own loomings to wander ravenous and doomed and mute as gorgons shambling the brutal wastes of Gondwanaland in a time before nomenclature was and each was all.”

As well, when McCarthy is describing an event he is absolutely brilliant. Here, a mercury spill:

“… the flasks broke open and the mercury loomed wobbling in the air in great sheets and lobes and small trembling satellites and all its forms grouping below and racing in the stone arroyos like the imbreachment of some ultimate alchemic work decocted from out the secret dark of the earth’s heart, the fleeing stag of the ancients fugitive on the mountainside and bright and quick in the dry path of the storm channels and shaping out the sockets in the rock and hurrying from ledge to ledge down the slope shimmering and deft as eels.”

McCarthy glories in the fact that he is, first and foremost, a consummate storyteller. His writing gathers strength from that fact, always facilitating the story. That is not to say that his formidable writing skills won’t pull you into the story. “A lone dark husbandman pursuing mule and harrow down the rainbow bottomland toward night.” The man paints with words.

The tone is set early. An itinerant revival preacher is charged with the rape of an 11-year-old and with having congress with a goat. Innumerable fights and other acts of violence erupt across the page. But all is smoothed and made whole with gentle lines such as “Egrets in their rookeries white as candle among the moss.” Besides, in the end the charges are not true and the reader is left simply with the energy and magnificence of the story. So the epic begins.

“When God made man the devil was at his elbow.” That short statement provides access to much of what compels this writer. He looks at man, peels back the layers of civilization with meticulous research and uncommon feeling and creates a base view of what drove America west and outward. He writes of a time when men didn’t have much materially other than what they carried, but they contained a pure sense of self, a strong creed of virtue and survival.

What is that southern knowledge of the Lord? I defy anyone to find the squalid kingdoms of mud McCarthy writes about. They don’t exist today in North America, don’t feature in the ken of his readers. But each reader will implicitly believe him. The sensual evocation of truth lilts in his descriptions.

There is an incipient racism throughout the text. It is the stuff western America was built on – Texas and the rest of the world, niggers, spics, injuns. McCarthy is hard on his native land but he has done the meticulous work to set this racism in its time, give his readers a window into the roots of western America. It is a chaotic picture, with the only constant being the undying belief in oneself, in the innate power of the rightness of being true to one’s nature. To read McCarthy is to understand that this is simply what it was to be Texan in 1850.

Manifest Destiny runs throughout, and perhaps an exploration of where today’s American militia movement finds its roots. “And mark my word. Unless Americans act, people like you and me who take their country seriously, while those molly coddlers in Washington sit on their hindsides, unless we act ….”

The book may be large but McCarthy’s words are sparse, dense and beautiful. He catches the foibles of man, the foolishness of an untrained life in one simple sentence from an old Mennonite viewing a young man dead in a bar fight. “There is no such joy in the tavern as upon the road thereto..” So simply he says it all.

And as the story progresses the Mennonite is one of those beacons that speaks briefly, but shines cognition on all that comes. Not heeded, but all-knowing in the simplicity of his vision of mankind.

It is probably not fair to liken some of the scenes of mass slaughter and destruction to Judy Chicago’s famous meat dress, but there is some of that in this work, death and destruction so transformed in art that it becomes something else. An understanding, perhaps, of how out-of-this-world the human condition sometimes is, of how strong man becomes when he knows himself, knows his place in this world, knows that he wants to create meaning out of chaos.

This is not the memory Americans have of the West, or how it was won. Old women with their heads blown half off, scalped for the “receipt.” Or governments that paid cash for those same “receipts,” thus ridding the Plains of bothersome First Americans. There is little of the gentleman here. These are men of base nature with all-purpose focused on the outcome, the yield. Dead is simply dead, what does the body or the saddles pouches offer up. There is no concern for propriety or Christian (or any other faith’s) rites – simply loot and leave.

After the major encounter with the Apache nation, the grievous wanton slaughter so elegantly splashed across the pages, the scalp hunters are entertained by the Mexican governor who had commissioned them. McCarthy lays bare the fact of all war, the vanquished are vilified and the victorious heralded far above their station – the societal absolution of murderers. We do it yet!

After the major encounter with the Apache nation, the grievous wanton slaughter so elegantly splashed across the pages, the scalp hunters are entertained by the Mexican governor who had commissioned them. McCarthy lays bare the fact of all war, the vanquished are vilified and the victorious heralded far above their station – the societal absolution of murderers. We do it yet!

An old concept now modern, one of McCarthy’s signature characters, Glanton, personifies the idea of living in the now. He runs his course, moment by moment with death destruction and craziness surrounding him. Always in the eye of the storm Glanton is reconciled to his fate, living all the harder because of the reconciliation. “Before man was, war waited for him.”

There is in this work a sense of the futility of man’s intervention. If God speaks it is in terms of the natural world, not the writer’s creed of man. McCarthy states, eloquently as always “ … the howl of the old dog wolf was the one sound they knew to issue from its right form, a solitary lobo, perhaps gray at the muzzle, hung like a marionette from the moon with his long mouth gibbering.”

Finally, throughout the novel there is the continuous unabashed in-one’s-face need to know. Part of it is place and McCarthy commands that with his superlative, inquisitive description.

We see the West in both macrocosm and microcosm. Part of it is spiritual, and the ex-priest character is always the counterpoint, probing the accepted. Most of all though, there is the judge. The judge is bent on his mission to be suzerain of the earth, to know all so he can understand all, and ultimately rule all. The judge’s quest is played in counterpoint to the rude death-dealing American scalp hunters he rides with, drinks with and murders with. Nothing is simple or clear in McCarthy’s work, layer upon wondrous layer.

To know is to command, in the same sense as Charles Olson’s dictum that to know one place, one thing impeccably, is to know everything.

McCarthy clearly knows what he is doing.

– Derryll White once wrote books but now chooses to read and write about them. When not reading he writes history for the web at www.basininstitute.org.