Home »

Kootenay girls trained to defend Canada

By Elinor Florence

Fearing an enemy invasion, thousands of Canadian girls as young as 16 joined volunteer militia groups across the country in the Second World War, learning how to carry out air raid warnings, fire weapons and even how to handle bombs. And some of them are still living right here in the Kootenays.

There hasn’t been much written about women’s militia groups, because they weren’t part of the armed forces and thus weren’t included in official military records. And women, as we all know, are often given short shrift in the history books.

So I was thrilled to discover that here in my own town of Invermere, at the Windermere Valley Museum, there exists a cardboard box filled with mementos of the local women’s militia group.

Better yet, the girl who served as the group’s secretary and painstakingly kept every scrap of paper associated with her group, is still alive and well. Her name is Joy Bond, formerly Joy Johnston, and she is 96 years old.

And another girl who served in the group is also still living here in town, Audrey Osterloh, formerly Cleland, aged 94. Here’s a photo of them at the Windermere Valley Museum, refreshing their memories of those long-ago days as defenders of freedom.

By sifting through the box of papers, and talking to Joy and Audrey, I learned a lot about what those plucky gals were up to back in the wartime years.

When Canada declared war against the Third Reich in September 1939, boys flocked to join up. Within a year, most graduating high school classes had emptied of young men, leaving the girls behind.

Naturally, many of them wanted to go, too. They were just as patriotic, just as capable, and just as eager to defeat the enemy. But women were not allowed to join the armed forces. So they got together and started their own quasi-military groups all over the country.

These had different names. Some of them were loosely attached to a central command; others were independent.

The Windermere Valley group formed in September 1941 with 20 members. They began by writing a letter to “head office” in Vancouver, the Canadian Women’s Training Corps. Head office mailed them some printed instructions, and provided moral support if little else.

The local group was Branch 10, one of 11 groups in British Columbia including Fernie and Cranbrook. (Not many people know that The Cranbrook All Girls’ Bugle Band was formed in 1941 as a women’s volunteer militia group. After the war, it was converted into a musical band.)

The local group was Branch 10, one of 11 groups in British Columbia including Fernie and Cranbrook. (Not many people know that The Cranbrook All Girls’ Bugle Band was formed in 1941 as a women’s volunteer militia group. After the war, it was converted into a musical band.)

While the boys in uniform were getting free room and board and a salary, these girls were paying their own expenses. The local group paid $1.50 each to join up, and then 25 cents per month. (To put that in perspective, head office reminded them that it was only the same cost as “one picture show”).

They also paid for their own uniforms, ordered from the Great West Garment Company in Vancouver – $23 for an officer and $13 for other ranks, consisting of a navy blue tunic and skirt, white blouse, black tie and gunmetal stockings, and low-heeled black shoes for drilling and marching. Most of the girls sewed their own uniforms.

The lead photo above is of the Invermere group, looking very smart and professional. Because it was a hot day, they were allowed to leave off their tunics.

Both Joy and Audrey are in this group, along with Phyllis Hunt, Alice Jones, P.M. Hewitt, Jean Blake, Doreen Johnston, Mary Dufault, Clare Docker, Edna Robson, Winnifred Weir, Dorothy Tegart and Eleanor Steele.

And lest you think it was easy to stand at attention, here are their printed instructions:

“On the command ‘SQUAD ATTEN-SHUN,’ bring the heels smartly together and in line, feet turned out at an angle of about 45 degrees, knees braced, body erect and carried evenly over the thighs, with the shoulders (which should be level and square in the front) down and moderately back. Arms should hang from the shoulders as straight as the natural bend of the arm will allow. Hands lightly closed (not clenched). Backs of the fingers should touch the thigh lightly, thumb to the front and close to the fingers and behind the seam of the skirt. Head erect, and eyes looking straight to the front and at their own height.”

Both Audrey and Joy had finished high school when they joined up. Joy was working at Invermere Hardware, and Audrey at the Imperial Bank of Canada. Other members were as young as 16, although they had to have a signed permission slip from a parent if they were under 18.

Both Audrey and Joy had finished high school when they joined up. Joy was working at Invermere Hardware, and Audrey at the Imperial Bank of Canada. Other members were as young as 16, although they had to have a signed permission slip from a parent if they were under 18.

This was no social club. They did not have teas, dances or parties. I venture to say that it required a commitment rarely found among young people today.

Training took place one night a week, for three hours. Compulsory subjects included Military Drill, First Aid, Stretcher Bearing, Morse Code, Motor Mechanics, Air Raid Precaution, Signalling, and Rifle and Target Practice.

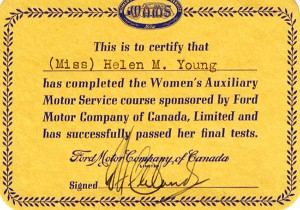

Above right is a certificate issued to Helen Young for completing a mechanic’s course.

The printed materials are daunting. For example, pages and pages of hand-written notes describe the types of bombs used by the enemy – whether explosives, incendiary or gas – their effects on the human body, and how to treat the victims.

The printed materials are daunting. For example, pages and pages of hand-written notes describe the types of bombs used by the enemy – whether explosives, incendiary or gas – their effects on the human body, and how to treat the victims.

But the girls studied hard. As one letter explains: “The subject of Air Raid Precautions has been dealt with so thoroughly that our instructors themselves said they could not pass the examination paper which was set.

“However, nineteen members wrote the exam and there was not a single failure. Eight members made over 90 percent, and six made between 80 and 90 percent.”

It may seem funny now to think that the girls were preparing for an enemy attack by the Japanese, but perhaps not so far-fetched.

The surprise attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941 showed that Japan was a force to be reckoned with. Everyone on the West Coast was on high alert, and that anxiety extended far into the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, and in varying degrees right across the country.

Right is an example of one propaganda poster that sent fear into the hearts of civilians everywhere, especially the ones in British Columbia.

Right is an example of one propaganda poster that sent fear into the hearts of civilians everywhere, especially the ones in British Columbia.

Perhaps that’s why the girls were eager to train themselves in the use of firearms. Here’s a letter from East Kootenay Divisional Commandant Major Kathleen T. Elkington of Fernie, who had served as an ambulance driver in the First World War.

She describes the musketry course, and concludes: “Please give Corporal White my salaams, and thank him for taking on this class, it is awfully good of him, and I feel sure that any of the girls will be able to ‘Pot Off a Jap’ when they arrive . . .”

Both the girls remember route marches up the long hill beside Lake Windermere, a distance of about five kilometres, wearing their skirts and their sensible shoes.

And they were expected to turn out for Church Parade, taking turns amongst the various churches. “We lined up and marched into church and sat down together, and then after church we stood up and marched out again,” Joy recalled.

Slackers were not allowed. If you didn’t attend regularly, you were dismissed. A look at this Parade Attendance sheet shows that meticulous track was kept of attendance. One girl was dismissed for being AWOL (Absent Without Leave) for three consecutive meetings.

As noted on her attendance sheet (right), Audrey Cleland received “disciplinary action,” but she couldn’t remember what for. “It was pretty hard to get into trouble when all the boys were gone,” she mused.

As noted on her attendance sheet (right), Audrey Cleland received “disciplinary action,” but she couldn’t remember what for. “It was pretty hard to get into trouble when all the boys were gone,” she mused.

The girls did more than train, living up to the motto on their cap badges Facta Non Verba, meaning “Deeds Not Words.” They made themselves useful by helping the Canadian Legion at the Armistice Day supper and the Vimy Ridge dance, hoisted and lowered the Victory Loan flag during that campaign, and showed up in full force at any wartime fundraiser.

They sent away hundreds of packages of cigarettes, and they collected bundles of magazines for British Commonwealth Air Training Bases on the prairies.

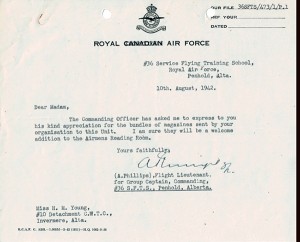

Here is one of many thank you letters they received, this one from the RAF training base at Penhold, Alberta.

Here is one of many thank you letters they received, this one from the RAF training base at Penhold, Alberta.

The girls earned military ranks similar to those of the armed forces, and were serious about completing the requirements to move on to the next level.

Joy remembers that she was proud to be made sergeant, which cost her five cents! She had to mail a nickel to Vancouver to receive her sergeant’s chevron, which she then sewed onto her uniform.

“I could have gone farther, but our leader Helen Young had the highest rank of Lieutenant. The next rank was Major, but Helen refused to become a major because her father had been a major in the First War, and even though he was already dead she felt it would dishonor his memory. So we all had to settle for a lesser rank.”

Here is a photo of the three top-ranking officers. Joy Johnston is on the left, Helen Young in the centre, and Eleanor Steele on the right. (Photo Credit: Windermere Valley Museum).

Here is a photo of the three top-ranking officers. Joy Johnston is on the left, Helen Young in the centre, and Eleanor Steele on the right. (Photo Credit: Windermere Valley Museum).

Here is an excerpt from an inspiring speech given to the group in May 1943 by that redoubtable leader, Helen Young:

“As far as summer holidays go, remember that war doesn’t take a holiday. Our soldiers, sailors and airmen don’t say: ‘It’s too hot to fight, let’s put it off until the fall.’ Our own Canadians, prisoners at Hong Kong, won’t be released for the summer. Have we then the right to take time off? Yesterday, we heard that a point on Vancouver Island had been shelled, today it is a point off the coast of Oregon.

“I don’t believe that this war will be won until every man and woman in the Allied Nations fights it, with everything they’ve got, Moral, Physical and Material, twenty-four hours a day!”

Very inspiring, indeed!

On July 2, 1941, Canada’s Parliament passed an Order-in-Council granting the Royal Canadian Air Force permission to enlist women. Within a matter of weeks, permission for the Canadian Army followed. Women had to wait another year before they could enlist with the Royal Canadian Navy.

But many militia girls joined the armed forces once they had the chance, including those from across the Kootenays.

Hats off to the members of the Canadian Women’s Training Corps, wherever they are now, and thank you for being prepared to defend our country!

– Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

– Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

Elinor’s first historical novel was recently published by Dundurn Press in Toronto. Bird’s Eye View is the only novel ever written in which the protagonist is a Canadian woman in uniform during World War Two. The heroine Rose Jolliffe is an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. She spies on the enemy from the sky and makes several crucial discoveries. Lonely and homesick, she maintains contact with Canada through letters from the home front. The book is available through any bookstore including Lotus Books in Cranbrook, and also as an ebook from any digital book provider including Amazon, Kindle and Kobo. You can read more about the book by visiting Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com/birdseyeview

Elinor’s first historical novel was recently published by Dundurn Press in Toronto. Bird’s Eye View is the only novel ever written in which the protagonist is a Canadian woman in uniform during World War Two. The heroine Rose Jolliffe is an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. She spies on the enemy from the sky and makes several crucial discoveries. Lonely and homesick, she maintains contact with Canada through letters from the home front. The book is available through any bookstore including Lotus Books in Cranbrook, and also as an ebook from any digital book provider including Amazon, Kindle and Kobo. You can read more about the book by visiting Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com/birdseyeview