Home »

Kootenay Park had conscientious objector camps

By Elinor Florence

Almost 11,000 Canadian men refused, mainly for religious reasons, to perform military duties during the Second World War. Instead, the federal government required them to do “alternate service” in work camps.

Almost 11,000 Canadian men refused, mainly for religious reasons, to perform military duties during the Second World War. Instead, the federal government required them to do “alternate service” in work camps.

Two of these camps were established in the 1,400-square-kilometre Kootenay National Park, located between Radium Hot Springs and the Alberta border.

Ray Crook of Invermere was not a conscientious objector. He was rejected from military service because of a heart murmur – ironic, since he will turn 99-years-old in September. He well remembers the wartime years, which he spent at his family homestead inside Kootenay National Park, working as a grader operator and truck driver, while his father supervised a group of conscientious objectors.

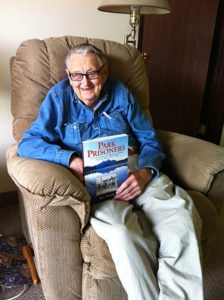

I spoke to Ray at his home in Invermere, and he gave me a copy of the book Park Prisoners: The Untold Story of Western Canada’s National Parks, 1915-1946, written by University of Saskatchewan history professor Bill Waiser, where I gleaned some further information.

Ray’s father Charles Crook homesteaded in the mountains about thirty kilometres east of Radium Hot Springs, inside an area that later became the national park. In 1932 he had the bright idea of erecting a gas station on his property.

Ray and his brother Charlie helped their father build seven log cabins, and Crook’s Meadows became a summer tourist campground that supported the family.

But the declaration of war put the brakes on their livelihood. Since gasoline was rationed, people weren’t driving anywhere on holidays, least of all to the remote mountain parks. Many people gave up driving altogether.

“When war broke out, Dad’s business was nil,” Ray recalls. “He was trying to pick up work wherever he could.” As a result, Charles Crook was happy to accept a position with the federal government, supervising conscientious objectors (sometimes called COs for short, or the more derogatory term coined during the First World War, “conchies.”)

They were sent to two camps inside the park – one called Sixteen-Mile Camp, and one called Twenty-One Mile Camp. Both were located on the banks of the Kootenay River. The men operated small sawmills and did other jobs in the park: fighting fires and building bridges and fixing roads.

Left is a photo of Charles Crook, right, with five of the conscientious objectors.

Left is a photo of Charles Crook, right, with five of the conscientious objectors.

The issue of Conscientious Objectors came about like this.

The Second World War lasted from 1939 to 1945. In 1940, the federal government brought in conscription, although not for overseas duty. All men could be drafted and trained for home guard duties, but only volunteers would be sent overseas.

But 11,000 men (only four percent of the total number of exemptions) refused to participate in any military training whatsoever, even for the home guard. Most of their objections were for religious reasons, so a compromise was reached with religious leaders: COs would be required to perform civilian labour for four months, the same length of time as standard military training.

Western Canada’s national parks provided both isolation and a healthy environment. Even better, the COs could enhance our parks to prepare for an expected increase in post-war tourism. They were paid 50 cents a day (well below the army pay of $1.30 a day), plus room and board, but they had to provide their own clothing.

COs included Mennonites, Hutterites, Doukhobors, Jehovah’s Witnesses and Seventh Day Adventists. There were also a few others from mainstream churches including Roman Catholics, Anglicans and Presbyterians. (As Ray remembers, there was even one German-Canadian who didn’t want to fight his own people.)

By May 1941, the work camps were ready to accept them. The two camps in Kootenay Park housed three main groups: Mennonites, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and Hutterites.

“The Mennonites were the first ones to arrive,” Ray recalled.

The Mennonite faith began in Europe around 1500, named after Menno Siemens. It is one of the historic “peace churches” committed to pacifism. To avoid persecution abroad, the Mennonites started arriving in Canada as early as 1786. Over two centuries, the Old Order Mennonites continued to shun technology and live traditionally, while others integrated into mainstream Canadian life.

When war was declared in 1939, there were about 110,000 Mennonites in Canada. Some Mennonites (like most Canadians) believed that the Nazis were purely evil and had to be subdued at all costs, while others refused any form of military participation.

It was a difficult situation that divided families, pitting brother against brother. About 60% of Mennonites who were drafted became COs, and the other 40% joined the armed forces. Some who chose to serve in the military were excommunicated by their churches after the war ended, while others died in battle.

The Mennonites who chose to follow pacifism were sent to work camps like the ones in Kootenay Park. They were hard workers, not a shirker amongst them, and they meekly accepted the hardships and isolation of camp life.

“They were nice people, very hard-working,” Ray said. “My Dad was a bush foreman for many years, and he said he had never worked with a bunch of finer young men in his life.”

“They were nice people, very hard-working,” Ray said. “My Dad was a bush foreman for many years, and he said he had never worked with a bunch of finer young men in his life.”

Ray Crook took the photograph of a road maintenance crew relaxing on the porch of a log cabin near Hawk Creek in Kootenay Park. The four men standing were conscientious objectors; the foreman holding the dog was Wally Lautrop; to his right is John Wells, the driver; and standing is Jim Long, the cook.

Ray himself became very friendly with these young men, who were about the same age. He worked as a truck driver at the time, hauling supplies into the camp.

“The accommodations were fairly primitive, just bunkhouses covered with tarpaper,” he said. During the coldest months of winter, the men almost froze.

“The food wasn’t bad,” Ray recalled. “Sometimes when I had to haul supplies into the camp, I sat down and ate with them.”

And although they were prisoners, they had infrequent leaves. “The workers were given occasional weekends off, and they got leave once or twice a year to go home and see their families.”

For many, it would be their first time away from their close-knit communities. Some of the men were married, with young children. The desperately homesick men amused themselves by singing hymns, writing letters home, reading, hiking, playing games such as horseshoes, and forming lifelong friendships. They were forbidden to speak German, although an old form of the German language was their native tongue.

They also laboured from sunup to sundown, in most cases with the most primitive hand tools. The lead image above is a photo Ray took of the men crossing Kootenay River on their way to fight a forest fire.

They also laboured from sunup to sundown, in most cases with the most primitive hand tools. The lead image above is a photo Ray took of the men crossing Kootenay River on their way to fight a forest fire.

This photo from Ray Crook’s collection shows the sawmill at Sixteen-Mile Camp.

By April 1942, when things were looking particularly bleak overseas and the Allies were in real danger of losing the war, the government ordered COs to serve for the duration of the war. (Unfairly, the men who had already completed their four months were exempt from further service.)

The next camp to open in Kootenay Park saw a different group of religious objectors arrive, mainly Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Jehovah’s Witnesses is an offshoot Christian denomination, directed by a group of elders in New York. The group emerged in the late 1870s and is known for door-to-door preaching, distributing literature such as The Watchtower and refusing military service and blood transfusions. They don’t observe Christmas, Easter, birthdays, or follow other customs considered to have pagan origins, and they believe that mainstream society is morally corrupt. Their refusal to serve in the military has caused them no end of trouble.

The Canadian government was less sympathetic towards Jehovah’s Witnesses than other denominations. From 1940 to 1943, their religion was banned in Canada, meaning they were convicted and sent to work camps. (By contrast, in Nazi Germany, the Witnesses were sent to concentration camps where many died.)

According to the book Park Prisoners, Jehovah’s Witnesses resisted alternative service, and were very unwilling workers. In fact, they were so uncooperative that Ray’s father finally quit his job, because he felt unable to work with them.

Their leaves were also restricted due to their habit of preaching, which was met with ill favour by local residents. “The Jehovah’s Witnesses, when they got a weekend off, would fan out across the valley and hand out copies of The Watchtower,” Ray recalls. “I don’t think they made too many converts.”

How did local residents react to the COs? Seeing these young, strong men enjoying relative freedom while your sons and brothers were fighting overseas must have been painful for some people. But Ray doesn’t remember any overt hostility towards the COs, although in the nearby town of Banff, the local newspaper complained about “conchies” and suggested that pacifism was “simply a cute method of saving their yellow hides.”

And residents were furious when they learned that the COs had been taken to the local hot pool for a swim. Here’s a photo from the book Park Prisoners. (It’s misleading to show them on this rare outing, since for the most part the COs led a very hard life.)

And residents were furious when they learned that the COs had been taken to the local hot pool for a swim. Here’s a photo from the book Park Prisoners. (It’s misleading to show them on this rare outing, since for the most part the COs led a very hard life.)

The third and final group to arrive were Hutterites.

At first the government was lenient towards Hutterites, but the public demanded they be treated like any other citizen. They accepted their fate meekly as a lesser of two evils, and performed their duties without complaint.

Hutterites are one of three major Christian Anabaptist groups (the others are Mennonites and Amish) surviving today, and the only group to insist on communal living. Hutterite history dates back to 1528 when a small group of German-speaking Anabaptists established a communal society in Europe to escape religious persecution. Under the leadership of Jacob Hutter, they established Hutterian beliefs, which they follow to this day: separation of church and state, communal ownership of property, and opposition to war. Hutterites have retained the dress and the language of their ancestors.

Ray took this photo of a Hutterite posing with a little boy, the son of the camp cook.

Ray took this photo of a Hutterite posing with a little boy, the son of the camp cook.

After the war ended in May 1945, the government refused to allow the inmates to go home until the last man returned from overseas. (Or perhaps the government was just trying to squeeze out a few more months of work). The last camp in existence was the one in Banff National Park, where the final inmate was released in July 1946.

And here’s an interesting update on Hutterite history.

In 2009, Ray Crook answered a knock on his door and found two Hutterite men. Just as many of us yearn to know how our fathers spent their wartime years, do did these two brothers named Paul and Sam Kleinsasser from Rose Valley Colony in Assiniboia, Saskatchewan. Here is Paul on the left, and Sam on the right.

“There was barely a trace left of the two camps in Kootenay Park,” Ray explained. “For a few years, the cabins were neglected and fell to pieces, and later the government bulldozed everything.”

The Hutterite brothers came to the right man, as Ray is perhaps the only living person who knows exactly where the camps were located. He drove with the brothers out to the park, and pointed them in the right direction.

There was once a telephone line running through the park, but it was removed decades ago. (Ironically, telephone service seventy years ago was better than it is today. Currently there is no cell service available in much of the park.)

But Ray remembered where the telephone line came into the main office, threaded through a piece of pipe. After several hours of searching, Sam Kleinsasser found the pipe still sticking out of the forest floor. He also found the cast-iron leg of a stove showing where the cook shack was situated, a pile of tin cans and some other remnants. And he even found a huge pile of sawdust where the sawmill stood.

Thus the Hutterite brothers learned exactly where their father had spent his long and lonely years. Sam Kleinsasser is fascinated by this period of Hutterite history, and hopes to write a book about it someday.

Here is a photo taken by Ray Crook of Sam Kleinsasser standing near the remnants of Sixteen-Mile Camp.

Here is a photo taken by Ray Crook of Sam Kleinsasser standing near the remnants of Sixteen-Mile Camp.

Finally, in another chapter of Kootenay Park history, Ray’s father Charles Crook was killed by a falling rock on November 20, 1945 and buried on his homestead. His grave was dug by COs from the nearby work camp.

In 1970 the mountain behind him was renamed Mount Crook. In 1987 Kootenay National Park declared the site as Crook’s Meadow Group Campground, and you can visit Mr. Crook’s grave and eat your picnic lunch nearby.

– Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

– Career journalist Elinor Florence, who now lives in Invermere, has written for daily newspapers and magazines including Reader’s Digest. She writes a regular blog called Wartime Wednesdays, in which she tells true stories of Canadians during World War Two. Married with three grown daughters, her passions are village life, Canadian history, antiques, and old houses. You may read more about Elinor on her website at www.elinorflorence.com.

Elinor’s first historical novel was recently published by Dundurn Press in Toronto. Bird’s Eye View is the only novel ever written in which the protagonist is a Canadian woman in uniform during World War Two. The heroine Rose Jolliffe is an idealistic Saskatchewan farm girl who joins the Royal Canadian Air Force and becomes an interpreter of aerial photographs. She spies on the enemy from the sky and makes several crucial discoveries. Lonely and homesick, she maintains contact with Canada through letters from the home front.

The book is available through any bookstore including Lotus Books in Cranbrook, and also as an ebook from any digital book provider including Amazon, Kindle and Kobo. You can read more about the book by visiting Elinor’s website at www.elinorflorence.com/birdseyeview.